SOURCE: THE TIMES UK

It’s been 30 years since conservation efforts to protect Uganda’s mountain primates began and their numbers have nearly doubled. Our writer seeks out the rangers, vets — and animals — who have made it possible

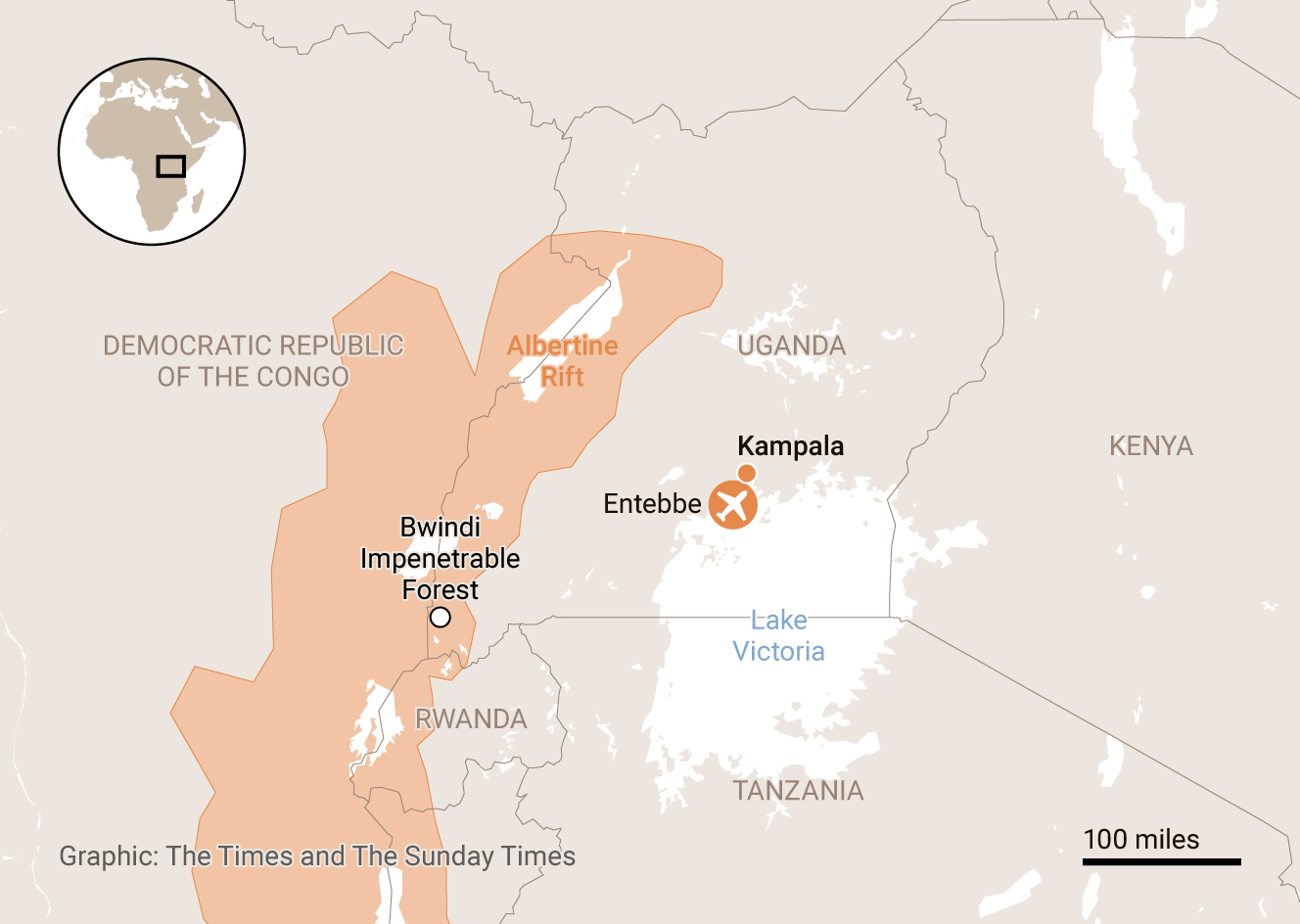

In a patch of isolated forest on the edge of east Africa’s Albertine Rift valley, creatures slink between the shadows of towering trees disappearing into a tangle of knotted vines. From dainty sunbirds to hulking primates, an astonishing array of species hide in the deep, dark depths of Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable Forest.

In her memoir Walking with Gorillas: The Journey of an African Wildlife Vet, published this month, the primatologist Dr Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka recalls revelling in the beauty of the green terraced hills of Buhoma, southwest Uganda. She first visited the region as a researcher in the mid-1990s and would later become the east African country’s first wildlife vet.

“When I finally arrived, the evening mist was rising,” Kalema-Zikusoka writes. “I felt like I had reached the ends of the earth.”

It has been 30 years since tourists first trekked to see mountain gorillas in Bwindi, a former reserve designated as a national park in 1991.

Researchers and government officials looked to neighbouring Rwanda for help against poachers. There, since 1979, gorillas had been habituated so they wouldn’t be startled by the sight of humans.

In the early 1990s the global population of mountain gorillas had dwindled to 600. Three decades later that figure has risen to more than a thousand, with over 50 per cent in Uganda. The remainder are spread between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, which lies to the west. The increase was proof that tourism can play a role in saving a species from the brink of extinction.

The Buhoma I encounter when I arrive on a soggy April afternoon is in many ways not so different to the raw, red-earthed settlement Kalema-Zikusoka describes in her book: smoke coils from mud brick kilns, women buckle beneath bundles of firewood and men strike heavy scythes into the fertile soil. In contrast to Rwanda, development here has been slow. There are fewer luxury hotels and infrastructure remains clunky. Kihihi, the nearest airstrip, is a 70-minute drive, accessible via a short flight from Entebbe.

GETTY IMAGES

Things are changing, though. Chinese money has smoothed over potholed dirt tracks with tarmac roads; the national carrier, Uganda Airlines, is poised to start direct flights between Entebbe and London this year.

Kalema-Zikusoka has also been busy making improvements to the lodge at the research centre she founded, Conservation Through Public Health (CTPH), where tourists can book full-board, en suite accommodation for less than £100 a night. There are four rooms available on an elevated wooden terrace with views of the mist-veiled forest, all named after gorilla troops.

My room is Mubare, named after the first family of primates habituated for tourism; I’m hoping to meet them during my stay.

During a tour of the laboratory where most of her work for the NGO takes place, Kalema-Zikusoka shares fond memories of Mubare’s well-loved silverback Ruhondeza, who died aged about 50 in 2012.

“He would deliberately set out to frighten tourists to see their reaction,” she says. “It was his idea of humour.”

Revealing more anecdotes, she lifts the lid of a chest freezer to reveal hundreds of test tubes containing faecal samples collected from the nests of all habituated gorillas. Each one is analysed under a microscope to check for microbes passed from humans, part of the conservationist’s work in establishing links between the health of gorillas and communities.

As well as improving community education about personal hygiene, her achievements include setting up HuGo, a human and wildlife conflict resolution team, and founding the fair-trade initiative Gorilla Conservation Coffee. In front of the research centre several farmers sift through beans ready for roasting. The finished product is sold in packets featuring an illustration of Kanyonyi, another superstar silverback from the Mubare line. In the near future Kalema-Zikusoka hopes to open a café in an open-air dining room above the research centre. Set at eye level with peaks veiled in mist, it has one of the best views in Buhoma.

So far 44 gorilla troops have been habituated for tourism — although not all are tracked daily — but many more wild apes, chimps and monkeys live in the forest. In 1996 no more than 12 tourists would be trekking in one day; now 160 tourists may be in the park at the same time.

Medad Tumugabirwe, who was a ranger in the park even before Kalema-Zikusoka arrived, was involved in habituating the Mubare group and has experienced the growth of tourism first-hand.

“At first the silverback Ruhondeza was attacking us,” he says, when we meet at the office for his Retired Rangers organisation, where he sits behind an empty desk below pages of hand-scribbled conservation commandments. “But slowly, slowly, week by week, month by month, he got used to us. Eventually he would send the babies towards us when he could see we were friends and not enemies.”

Initially gorilla permits cost only £121, but there was no guarantee the rangers could locate the animals so that tourists could see them.

“Communication was a very big problem,” explains Tumugabirwe, who retired last year. Without any radio equipment, gumboots or rain jacket, he would trek barefoot through stinging nettles and ants’ nests, occasionally staying out past midnight to check on the gorillas’ location.

Despite the hardships he endured, 30 years later the agile 60-year-old still feels young. Currently seeking funds through a Kickstarter campaign, he hopes his NGO will provide an emotional and financial support network for retired men and women with plenty of energy still left in their tanks. “I dream about gorillas,” he confesses, his voice trembling with mixed emotions of pride and sadness. “My life was — and still is — gorillas.”

Mubare’s original members have either died or joined other families, but I plan to meet a new generation — Mubare’s nine descendants — the following morning. In contrast to Tumugabirwe’s early days, gorilla trekking is now a far smoother, carefully orchestrated experience: a maximum of eight tourists is assigned to each troop, who will have been closely monitored by trackers since first light.

“They’re not shy,” warns Amos Nduhukire, our ranger, as he shows us a family tree of Mubare’s current members during a briefing at the park’s headquarters. “They’ll run between your legs.”

GETTY IMAGES

After a short drive to reach the unmapped village of Kanyerere, we begin our trek through farmland. Mud brick houses peek from behind the fanning leaves of banana plants on a crush of hilltops. Women dressed in bright kitenge fabrics are bent double sowing potato seeds for harvest. On pathways children have laid out sketches of gorillas for sale. A revenue-sharing scheme means 20 per cent of all park fees are invested in surrounding communities, along with an additional £8 of every £565 permit going to those living close to Bwindi.

A couple of hours after slipping and sliding on steep forest trails matted with tree roots, we mask up (a new rule introduced during the pandemic) and prepare for our one-hour audience with the gorillas.

Tumbling from the bushes, juveniles roll past our feet, making it tricky to keep the required 10m distance. Staring at his reflection in my camera lens, one toddler points a thick, stubby digit in my direction. But he’s soon distracted by a sibling pouncing playfully on his back. More interested in foraging for fresh leaves, his mother scales a fig tree.

Submerged in nettles, the silverback Maraya is indifferent to his human visitors. Barely lifting an eyelid, the alpha ape fiddles with his belly button before mounting a female and grunting pornographically.

“I told you they weren’t shy,” sniggers Nduhukire, as the big daddy lets rip an explosive fart.

Without doubt habituation has altered the behaviour of these animals, making them less wild. One of the biggest contentions between leaders in conservation and tourism is whether more gorillas should be habituated. Nelson Guma, Bwindi’s chief park warden, says there are no plans for further habituation. Splits in existing families are creating enough groups to meet demands. He also hints at a possible increase of permit prices to “harmonise” with Rwanda’s £1,210 fee.

When we meet at his office next to the park gates in Buhoma, he admits Uganda’s success has also brought challenges, including increasing pressure on space as both gorilla and human communities grow.

“When you remove the fear of humans from gorillas, they go to where people are,” he says, outlining plans to clear thick areas of vegetation within the forest to make them more accessible to gorillas. Forcibly moving villages to create a buffer zone would be a last resort.

Understandably it’s a sensitive topic. Controversially evicted from Bwindi in the early 1990s, the Batwa hunter-gatherer community has never fully adapted to a new world. Groups continue to campaign for rights to re-enter the forest and perform traditional ceremonies, but the risk of transmitting diseases to the animals, who are genetically close to humans, is too great.

And here lies the great contradiction of habituation efforts: despite years of trying to bring people and gorillas together, it’s imperative they stay apart.

Yet Kalema-Zikusoka thinks the necessary evil of tourism isn’t quite the demon it’s made out to be. Weighing up the pros and cons back at the CTPH’s scenic dining area, she admits all arguments boil down to the same conclusion: mountain gorillas are the only gorilla subspecies whose population is growing.

Nodding in agreement, I watch the peaks of extinct volcanoes ghost into the horizon and listen to the fading calls of roosting colobus monkeys as dusk falls. Bwindi is derived from the word Mubwindi, which means “place of darkness” in the local language Runyakitara. But the thriving forest I see below me has evolved into a sanctuary penetrated by rays of light.

Sarah Marshall was a guest of Great Lakes Safaris, which has five nights’ B&B from £1,873pp, including domestic flights, one gorilla trek permit and some extra meals (greatlakessafaris.com). Fly to Entebbe