SOURCE:  | 05/05/2025

| 05/05/2025

©FAO/Rewild

In the misty hills surrounding Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Gorilla Conservation Coffee is demonstrating how sustainable agriculture can simultaneously protect endangered wildlife and empower local communities. The enterprise, one of eleven pioneering startups supported by FAO’s SDG Agrifood Accelerator Programme, is helping smallholder coffee farmers to prosper while contributing to conservation efforts in this biodiversity-rich region.

The SDG Agrifood Accelerator Programme, which ran from 2022-2024, provided assistance for innovative startups that are transforming agrifood systems by enhancing environmental protection and improving the lives of marginalized members of their community. Participating enterprises received tailored mentoring, tools to measure and amplify their impact and small grants, to enable them to scale up their business while enhancing their contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The Programme was implemented with the technical support of SEED.

Transforming Communities through Sustainable Agriculture

Gorilla Conservation Coffee is a social enterprise dedicated to improving the livelihoods of smallholder coffee farmers living near Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda, while protecting the endangered mountain gorillas that call the forest home. They pay coffee suppliers a premium price and encourage sustainable agricultural practices, which reduces the need for farmers to resort to activities that damage the forest, such as poaching or wood collection. This in turn helps protect the gorillas and their habitat.

Participation in the SDG Agrifood Accelerator Programme enabled Gorilla Conservation Coffee to make significant strides in both business growth and sustainable development:

Building knowledge and skills

|

|

© FAO/Rewild

The enterprise delivered training to 145 farmers – including 120 women farmers and 25 model farmers – in sustainable agricultural practices and post-harvest handling. The training focused on improving yields through climate-resilient farming techniques while supporting environmental conservation. Using a peer-to-peer approach, these trained farmers have become mentors, sharing their knowledge with 355 additional farmers, with a particular focus on youth and reformed poachers. Through this model farming approach, the initiative has successfully reached 500 farmers in the area, creating a sustainable network of agricultural knowledge and expertise.

Infrastructure for growth

87ee5db8-b14b-4132-8466-ed857de88141.jpg?sfvrsn=69faecc5_1) |

.jpg?sfvrsn=d313b224_1) |

© Gorilla Conservation Coffee

The FAO grant funded critical infrastructure improvements that transformed local coffee processing. New motorcycles, pulpers, and water tanks have made market access easier for local farmers. Previously, 150 farmers had to transport their coffee long distances over challenging terrain to reach buying centres. The new processing facilities not only reduced this burden but also decreased post-harvest losses. These improvements created jobs for local youth and have enhanced the quality of locally processed coffee.

Climate-smart agriculture

|

.jpg?sfvrsn=561b6f39_1) |

© Gorilla Conservation Coffee

Recognizing the importance of climate action, the Programme facilitated the introduction of agroforestry practices among coffee suppliers. With the support of 145 coffee farmers, over 7000 shade tree seedlings were planted. These shade trees help protect both the coffee crops and the surrounding environment, preventing land degradation. They will also help to boost yields.

SDG Impact

| Farmers have increased their yields and income through improved agricultural practices. | |

| The enterprise engages and trains women farmers in sustainable agriculture practices. | |

| New buying points and processing facilities have created local employment opportunities for youth and women. | |

| Marginalized groups, including women and youths, have found new income-generating opportunities in the coffee value chain. | |

| Local communities are engaged in conservation efforts and sustainable agricultural practices. | |

| Sustainable farming techniques and new infrastructures have minimized post-harvest losses | |

| Agroforestry initiatives and sustainable land-use practices have contributed to climate resilience and biodiversity conservation. |

Looking forward

The FAO SDG Agrifood Accelerator Programme has provided Gorilla Conservation Coffee with both financial support and tools for monitoring their social, economic, and environmental impact. This integrated approach helps ensure that their business growth aligns with the SDGs.

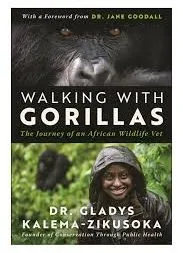

Dr Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka, Founder and CEO of Gorilla Conservation Coffee, shared the enterprise’s vision for the future: “We greatly appreciate the support from the FAO SDG Agrifood Accelerator Programme, which provided critical funding that reduced the distance farmers had to travel to transport coffee to buying and processing centers. This support also enabled us to train our women coffee farmers and model coffee farmers in climate-smart agriculture. We plan to train all our 630 coffee farmers in agroforestry, including 230 women. As our working capital increases, allowing us to buy farmers’ premium and specialty coffee at above-market prices and sell it in Uganda and internationally, we aim to double the number of coffee farmers we currently engage in sub-counties surrounding Bwindi Impenetrable National Park. This expansion will further reduce poaching and wood collection in the forest habitat of the endangered mountain gorillas.”

As Gorilla Conservation Coffee scales its operations, its progress highlights how strategic investments and capacity-building through initiatives like the SDG Agrifood Accelerator Programme can benefit communities, the environment and businesses alike. Their journey offers valuable insights for other enterprises working to combine conservation efforts with sustainable agricultural development.

| Saturday, September 21, 2024 By

| Saturday, September 21, 2024 By