Dr Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka says she “felt a deep connection” after her first encounter with mountain gorillas. It was in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park and she was “conducting research as a veterinary student at the Royal Veterinary College, University of London.”

At once, she was intrigued by the “gentle giants” if anything because they are “highly intelligent and social animals with complex family structures.”

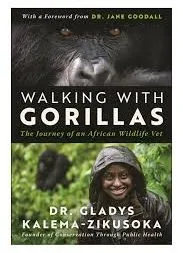

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka, who is the founder and chief executive officer of Conservation Through Public Health (CTPH), says the great apes “exhibit emotions and behaviours similar to humans, which makes them incredibly fascinating to study and work with.”

Such is the uniqueness of gorillas that their survival, says Dr Kalema-Zikusoka, “affects the health of the entire forest environment.” Conserving them is, therefore, a no-brainer, at least in the book of Kalema-Zikusoka. The forest ecosystems whose health the great apes maintain “are vital for the broader environmental services that benefit both local and global populations.”

Then there are the economic benefits. Dr Kalema-Zikusoka chooses to use the adjective ‘profound’ when describing them. “Twenty percent of the park entry fee and $10 (Shs37,000) from every gorilla permit is put aside to support community development.”

The increase in the number of mountain gorillas from 650 to 1,063 across the past 27, commendable as it seems, feels like a drop in the ocean. Dr Kalema-Zikusoka, who has the distinction of being Uganda’s first wildlife veterinarian, is not under any illusions. Her gentle giants— found only in Uganda, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)—remain “endangered or critically endangered.”

“Another significant threat particularly as the population of mountain gorillas is grows due to successful conservation efforts, is reduced habitat due to high human population growth rates and agricultural expansion,” she says, adding: “Poaching, although reduced, still remains a threat in some areas. Addressing these threats requires a multifaceted approach, including disease prevention, community engagement and habitat protection.”

Park rangers, whom Dr Kalema-Zikusoka describes as “the frontline defenders of our natural heritage”, cannot be celebrated enough. They help preach the gospel of conservation and “working collaboratively to find sustainable solutions to human-wildlife conflicts.” They do all this under challenging circumstances.

“Through the support of generous donors, CTPH trains the rangers to monitor the health of gorillas and other wildlife, including preventing disease transmission between people, wildlife and livestock through a One Health approach,” Dr Kalema-Zikusoka discloses.

“CTPH works with the rangers to offer health and veterinary services to ensure both the rangers and the wildlife they protect remain healthy. With support from donors, CTPH also supplies equipment and technology such as GPS devices, camera traps and communication tools, including smart phones to enhance their ability to monitor and protect wildlife,” she adds.

CTPH promotes biodiversity conservation by enabling people, gorillas and other wildlife to coexist through improving their health and livelihoods in and around Africa’s protected areas and wildlife-rich habitats.

“We founded CTPH in 2003, after recognising the interconnectedness of wildlife health, human health, and conservation. While working as the first veterinarian for the Uganda Wildlife Authority, one of my first cases was a fatal scabies disease outbreak in then critically endangered mountain gorillas, which was traced to the local community living around the park,” she says.

She adds: “This made me realise it was not possible to keep the gorillas healthy without improving the health of their human neighbours. By improving the health of people and animals together, we could protect the gorillas, creating a win-win situation.”

During a tour of the lab at the Gorilla Health and Community Conservation Centre where most of CTPH’s work takes place, the CTPH Wildlife Health and Laboratory technician, Annaclet Ampeire, says their laboratory is a research facility and it helps them in gorilla health monitoring.

“Every month, we monitor all the habituated gorilla families in Bwindi and Mgahinga national parks through non-invasive faecal sample collection from gorilla night nests for analysis in this lab to find out if there is a zoonotic disease outbreak,” Ampeire reveals.

“We do this as an early warning system to detect possible zoonotic diseases that may be transmitted from humans and livestock to gorillas, and vice versa. If we find zoonotic diseases that have been transmitted from humans to wildlife, we carry out two community interventions. One, we collect livestock faecal samples, analyse them and treat the livestock. Two, we collect human stool samples together with medical staff of the nearby health centres, analyse them and treat the people,” Ampeire adds.

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says CTPH’s work revolves around collecting gorilla faecal samples. The samples, she adds, “provide invaluable data on the health of the gorilla population.” This includes, but is not limited to “the presence of disease-causing pathogens, stress levels, and their diet.”

By regularly monitoring such indicators, CTPH can take proactive measures to prevent disease outbreaks “particularly between people, gorillas and livestock.” It can also “ensure the long-term survival of this endangered species.”

CTPH also runs an initiative of Village Health and Conservation Teams (VHCTs). Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says: “VHCT coordinators are the backbone of our community-based health and conservation initiatives. They are responsible for training and mentoring village health and conservation team members, facilitating health education, and ensuring both human and wildlife health are monitored and addressed at the community level. Their work is vital in bridging the gap between conservation and public health.”

She adds: “They also collect quarterly data from other VHCTs, which our community health and conservation field officers then send to our monitoring and evaluation department for central management and decision-making. During the Covid-19 pandemic, a section of VHCTs were trained to become members of the village Covid-19 taskforces and led the taskforces in 59 villages to carry out community surveillance, referrals and home-based care as per the Ministry of Health guidelines.”

Kate Namusisi is a VHCT coordinator. Before entering her home in Kwenda Cell, Buhoma Town Council in Kanungu District, she requests us to wash our hands using the tippy tap hand washing device placed in her compound.

“It is important to wash your hands before entering one’s house to avoid transmitting germs or other disease organisms,” she says.

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka describes Namusisi as “an exemplary and trusted leader in her role as the VHTC team coordinator of Mukono Parish in Buhoma Town Council.” The two have worked together for many years.

“The VHCT programme has had a significant impact on both human and gorilla health. By improving access to healthcare and health education in remote communities, we’ve seen a reduction in disease transmission between humans and gorillas,” Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says, adding that communities have been empowered along the way, with VHCTs growing from 26 in 2007 to 430 this year.

While growing up, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka was surrounded by pets and would eventually become a veterinarian in her adulthood. After graduating as a veterinarian from the Royal Veterinary College (RVC), University of London, she returned home to become the first wildlife veterinarian for the Uganda National Parks (UNP), now Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA). She also set up the veterinary department at UWA.

“I grew up with lots of pets at home – the usual cats and dogs, and they became my companions. When they got sick, I hated seeing them suffering and would miss school to go with my mother to get the animals treated at the small animal clinic at Wandegeya in Kampala. By the age of 12, I had decided that I wanted to become a veterinary doctor,” she says

“When I was in Senior Six at Kibuli Secondary School, I got an opportunity to revive the wildlife club as the chairperson. We took the students to Queen Elizabeth National Park, a magical time and a turning point in my life where I decided to become a veterinarian who can also bring Uganda’s wildlife back to its former glory. This deep empathy for animals, combined with a passion for science, eventually led me to pursue veterinary medicine as a way to make a tangible difference in their lives,” she adds.

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka met her future husband, Lawrence Zikusoka, in North Carolina, and they got engaged in March 2001. Gladys and Zikusoka had their traditional introduction ceremony (kwanjula) at her ancestral home in Kiboga District on July 28, 2001. They got married at All Saints Cathedral in Kampala on August 4, 2001.

“Balancing family life with my work at CTPH has been challenging, but I’ve managed by trying my best to stay organised, prioritising tasks, and relying on a strong support system. My family understands and shares my passion for conservation, which makes it easier to manage these dual responsibilities,” she says.

She adds: “My husband is one of the founders of CTPH and was the first donor, so he understands and appreciates my journey in conservation. We intentionally engage our two sons, Ndhego and Tendo in our conservation work, and they have developed a passion for animals and nature, as well as developed long lasting relationships with the local children at Bwindi Impenetrable National Park.”

| Saturday, September 21, 2024 By

| Saturday, September 21, 2024 By