SOURCE: FINANCIAL REVIEW

Dr Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka recalls a cheeky monkey that inspired her younger self to dream big. Today, as the country marks the 30th anniversary of gorilla tourism, she’s a key reason for its success.

Uganda’s great apes owe a debt of gratitude to a pet vervet called Poncho. The monkey belonged to the Cuban ambassador to Uganda in the 1970s; he would sit on the gate of the neighbouring house in Kampala, where a young Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka lived with her family.

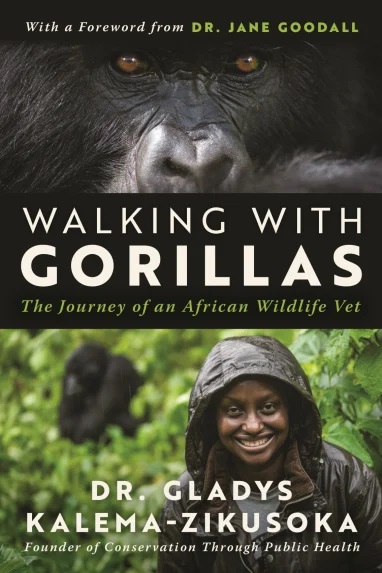

“I was fascinated by his fingers and fingernails that looked exactly like mine – so human,” she writes in her recently published memoir, Walking with Gorillas: The Journey of an African Wildlife Vet.

“He was my first venture into studying primates.”

It was a time of tremendous political upheaval. Kalema-Zikusoka’s parents had both been involved in politics; when Idi Amin staged a coup in 1971, her father – a tireless advocate for social upliftment and a member of the overthrown government – was assassinated.

“I was only two years old, so I never got to know him,” she says. “And writing the book, I realised he had had so much impact on my life.”

“I got to understand the role of tourism in conservation and how communities are benefiting from tourism,” she says.

This positive impact had been demonstrated in neighbouring Rwanda, where gorillas were attracting crowds. Uganda, by comparison, was flailing – even though about half the mountain gorilla population – now estimated to number 1063 – is found in Uganda (they also range across the Democratic Republic of Congo).

The experience also underlined the risks inherent in human-gorilla interaction: shared DNA renders great apes susceptible to human-borne diseases. As tourism improved, so the risks to habituated gorillas increased. After her stint at Bwindi, Kalema-Zikusoka presented a report to the then executive director of Uganda National Parks, Dr Eric Edroma, outlining the risks and the critical need for a dedicated wildlife vet. He told her that when she graduated, the job would be waiting for her.

The following year, degree in hand, she returned home and set up a vet unit with the Uganda Wildlife Authority.

“There were so many firsts,” she recalls. “No-one thought you should even touch a wild animal to treat it. It was always [about] breaking barriers. I’d meet resistance, but then I’d also meet people who were supporting me. I worked with them, and we’d get it done.”

Kalema-Zikusoka shaped her job description on the run: one day she’d be translocating giraffes, the next she’d be deep in the rainforest removing a snare from a gorilla’s limb. In-between, she married and had two children, lobbied for funding and built networks with government departments, academics and conservationists including primatologist Dr Jane Goodall. In the forward to Kalema-Zikusoka’s book, Goodall calls her an “inspiring example” who “has made a huge difference to conservation in Uganda”.

Soon after the vet unit’s launch, the intractable link between human and gorilla health was amplified when a baby gorilla died during a scabies outbreak. The infection was traced to impoverished communities living on the park’s periphery; gorillas would often forage in their gardens. CTPH was established in response to the predicament, and in the two decades since has achieved untold success.

“We’ve made a lot of progress,” Kalema-Zikusoka says. “Gorillas are herded back [from community land] before they get sick. Since people are getting more healthy and hygienic we haven’t had a scabies outbreak, [and] giardia has almost disappeared in the gorillas. And as we attend to people’s health and their needs, they care more about the gorillas because we show them that we are not only concerned about the gorillas and the forest and the wildlife, but we also care about them. So, they’re more likely to want to protect the wildlife.”

Such is CTPH’s success, it has won international funding and recognition for its work – which now includes environmental preservation, family planning programs and support for sustainable agricultural practices such as the coffee project. A laboratory monitors gorilla health and a community lodge offers accommodation overlooking a ripple of mist-plugged valleys at Buhoma, Bwindi’s primary gateway.

When COVID-19 struck in 2020, CTPH rose to yet another seemingly insurmountable challenge. Appointed to the government’s COVID-19 taskforce, Kalema-Zikusoka was able to prioritise an immunisation program for rangers and insist on mandatory vaccinations for tourists. She’d long lobbied for a mask mandate for gorilla tourists, and the pandemic helped facilitate this directive. But Bwindi’s habituated gorilla troops remain exposed.

“[Tourists are] wearing masks, but they still want to get close to the gorillas,” she says. “We are continuing to test for respiratory viruses, but also looking at other things like bacteria, salmonella, typhoid.”

And though the great apes have demanded the lion’s share of her time, Kalema-Zikusoka hasn’t forgotten the residents of Queen Elizabeth National Park, where her dream to become a wildlife vet took root all those years ago. Now stable, its lion population is nonetheless vulnerable. As tourism has cast a lifeline to gorillas, so she hopes it might change the fate of wildlife in Uganda’s lesser-known parks.

“The savannah parks are not getting enough tourists,” she says. “It is not enough just to see the wildlife – if you visit the communities, they’re less likely to kill the gorilla, the chimp, the lion, the elephant.

“Once a community member meets a tourist, they’re much less likely to poach, much less likely to destroy the habitat.”

As once a curious child who encountered a pet vervet and a park bereft of lions was wont to choose an unconventional path – one that would change the course of Ugandan conservation.

Catherine Marshall travelled to Uganda as a guest of the Uganda Wildlife Authority.