Published at August 18, 2023 by Catherine Marshall

Source:The Age

Somewhere high above me, the mountains are touching the sun. They sweep heavenwards like mighty barricades, their flanks cloaked in a tangle of forest, their peaks concealed in a pall of cloud.

“We expect the baptism every time,” warns guide Amos Nduhukire.

But this forest’s density is self-evident; enmeshed vegetation will surely shield us from the deluge as we penetrate its understory. Ahead of us lies a path swaddled in vines, spongy with accumulated rainfall. We must step carefully lest we slip, we must duck and swerve to avoid the forest’s probing tentacles.

A sound emanates from deep within: a pulsating wheeze, a baritone groan. It erases the symphony of insectile clamour and gentle birdsong. Nduhukire pauses. The sound comes again. He plunges into the undergrowth, beckoning me to follow. As we pass through a clearing, I realise the baptism he warned of was overstated: the clouds are rising slowly, like a bride’s veil; revealed beneath them are slopes damp with morning vapour. But a religious encounter of sorts awaits, for our trackers have located the source of those reverberations: a family of endangered mountain gorillas secreted deep within the foliage.

It’s 30 years since the first gorilla tourist arrived in Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, a World Heritage Site wedged into the Albertine Rift in the country’s south-western corner. Nearly half the world’s 1063 remaining mountain gorillas live here; the rest range between Uganda’s Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, two hours’ drive south, and neighbouring Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Driven largely by this flagship species, tourism accounted for nearly eight per cent of Uganda’s GDP prior to the pandemic. The socio-economic benefits of gorilla tourism cannot be overstated.

“Making 30 years has been a very interesting journey,” says Lilly Ajarova, long-time conservationist and chief executive of the Uganda Tourism Board. “Tourism has changed everything, especially for the people living around the national parks… Fifty-eight per cent of those employed in tourism are women, which gives a good opportunity for gender equality.”

But there’s an elephant in the gorilla-scented room: equality isn’t guaranteed for Ugandans – or tourists. Recently, President Yoweri Museveni signed into law an act that criminalises same-sex relationships; prison sentences and the death penalty are potential consequences. While some groups are calling for a tourism boycott, others argue such action would punish the communities and wildlife whose welfare depends on foreign visitors.

Museveni’s decree comes hot on the heels of another scourge, COVID-19. Not only did tourism cease during the pandemic, gorillas – which are highly susceptible to human-borne disease – faced potential extermination. This danger was exemplified at San Diego Zoo Safari Park, where captive gorillas caught COVID-19 (they recovered with onsite care).

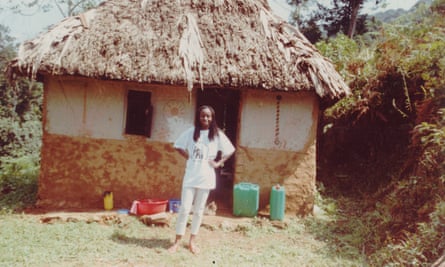

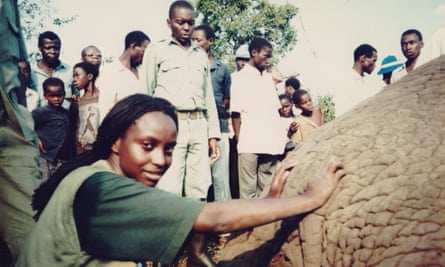

Fortunately, such calamity was avoided in Uganda; the rangers who monitor habituated gorillas received priority vaccinations and were equipped with masks and sanitiser. Though long mandated in the Republic of Congo (home to critically endangered western lowland gorillas), a Ugandan tourist mask directive was finally catalysed by the pandemic. For the preceding decade, such action had been urged by the country’s first wildlife vet and founder of Conservation Through Public Health (CTPH), Dr Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka.

“There was a tug of war about mask wearing,” she says. “Uganda and Rwanda were competing for tourists. [People] were concerned – ‘What if tourists don’t want to come, because we’re making them wear masks?’ COVID forced the issue.”

During the pandemic, Kalema-Zikusoka’s team built on a foundation laid decades earlier after a baby gorilla died during a scabies outbreak. The incident underscored the intractable link between gorilla and community welfare; CTPH was founded as a response to these twin issues. Today, the program includes COVID-19 prevention measures, family planning advocacy, educational programs and a coffee-growing project for farmers living on Bwindi’s periphery; visitors can order the fair-trade brew at Kalema-Zikusoka’s Gorilla Conservation Cafe in Entebbe, or meet farmers during one of her coffee safaris. Such community uplift has helped reduce human-wildlife conflict. By addressing socio-economic problems, she says, gorillas can thrive.

“Uganda and Rwanda are the two countries in the world that have a lot of gorilla tourism and where gorilla tourism is contributing significantly to the national economy. It’s running all the other parks that don’t have enough tourists to meet operational costs. Gorillas, they’re like the lifesaver.”

But they’re not the only primates with such lifesaving potential: endangered chimpanzees also inhabit Bwindi, and while the park’s jagged terrain makes them difficult to track, conditions are wholly amenable in Kibale National Park, five hours’ drive north. This is where my own wildlife encounter starts, after a journey by road from Kampala across grasslands sporadically dotted with villages, over hills glossy with tea plantations and into the folds of the tropical forests where Kibale’s chimps live. They’ve left calling cards: shredded seed pods and leaves strewn across the forest floor.

“Good news,” says guide Alex Turyatunga. “The chimps are moving here. They are asking, ‘Where are you?’ Their telephone is now on.”

It’s the red colobus monkey’s call that rattles the rubber trees and echoes through the forest in a haunting melody. Vines hiss and sigh; birdsong glances off the canopy. It’s easy to slip unseen into this fecund underworld, to lay a snare and feed one’s family with the bush pig or duiker caught in it. But chimps are often the unintended victims of this outlawed practice.

“People were redundant [during the pandemic], and most of them would sneak into the forest and put in traps, and as chimps move on they get trapped. We have a vet doctor, and they come and dart the chimp and remove the snare. That’s one of the biggest challenges,” Turyatunga says. “Two, we’ve got a challenge of chimps moving outside of the forest. The whole of this park is surrounded by communities, so chimps have the habit of going outside to look for sweet things – sugar cane is the number one. You expect them to visit you if you have a garden. Then if you have beehives they also go for honey. People may spear and kill them.”

Tourism is a vital resolution; it provides employment for people like Turyatunga along with explicit revenue-sharing schemes.

“Twenty per cent of annual collections go back to the communities neighbouring the park, such as they become stakeholders in conservation,” he says. “I’m born around [here], so I’ve got a job here, my livelihood is here. Any chimp out there, they say ‘Alex, your chimps are here’. But they don’t know they’re all our chimps.”

And their call, when it comes, is all-encompassing. The stillness is ruptured by a blood-curdling shriek as a juvenile chimp torpedoes through the leafy awning. Angered at his diminished hierarchical status, he sinks his sabre-teeth into the fruit of the aptly-named “testicle tree”. Nearby, the alpha male regards me with a look of distinct familiarity. It’s another baptism of sorts, an encounter with our closest living relatives (along with bonobos).

Emerging from the forest, I’m comforted by the altogether gentler demeanour of the youngsters sharpening their hospitality skills at Cafe Kibale, near the trekking entrance. They brew coffee grown on nearby slopes, prepare tasty Ugandan fare and, in quiet periods, take modules on wildlife studies and conservation.

The cafe was founded last year by Great Lakes Safaris Foundation in an effort to address high unemployment and share tourism’s burgeoning potential with local communities. Its founder, Amos Wekesa, knows well the power of education: born during Idi Amin’s dictatorial reign in the 1970s, he was given an opportunity to attend school after the Salvation Army visited his parents’ village in eastern Uganda. He later studied tourism and worked in the industry as a cleaner, messenger and tour guide while saving up enough money –$US200 – to start Great Lakes Safaris in an “under-the-staircase” office in 2002.

“I first went to track gorillas in 1999. It was tough, accommodation was rough, the quality of guides was not as good as they are today,” he recalls. “The roads, of course, some parts are still rough, but it’s much better today than they were at the time. A lot has improved.”

Wekesa has enlarged that potential; today, his Uganda Lodges portfolio includes properties in three of the country’s national parks – including Primate Lodge, the only accommodation located within Kibale’s boundaries. Graduates of his training program will fill the employment gap here and at other Ugandan tourism ventures.

“The first graduation [in June 2022] was so good, they shocked me. It shows that anybody can be anything. Their parents were like, ‘Ah, no, there’s no hope for my kids’. And of course we’d just come out of COVID. It’s expensive, but it’s value I’m giving back. The idea is, everywhere we have a lodge, we’re going to do the same. If we’re able to train 200 people every year we’ll be very happy,” he says.

“You know, Uganda was the top tourism destination in Eastern Central Africa until [Amin’s coup in] 1971. It can go back to its old glory.”

That glory is distilled days later as I track those gorillas in Bwindi.

“We can do our last preparation right now,” Nduhukire says. “Let’s make sure we have no flash in our cameras. Once you’re done with a sip of water you can put on your mask, and we’ll go straight to the gorillas.”

We approach in supplication these tender creatures whose future lies entirely within human hands. Haloed in greenery, a silverback lifts a frond to his bearded maw. Above us, a female dangles gymnastically from a tree. Nearby, a baby dozes on a branch’s hollow. Her name is Miracle, Nduhukire says, and this she is. Born at the pandemic’s outset, the tiny gorilla is at once a talisman, an expression of hope and a manifestation of glory.

THE DETAILS

Fly

Emirates flies daily from Sydney and Melbourne to Dubai, with regular connections to Entebbe. See emirates.com.

Stay

Great Lakes Safaris’ seven-day gorilla and chimpanzee safari costs from$5200 a person and includes trekking permits, games drives, transfers and accommodation at the operator’s lodges in Bwindi, Kibale and Queen Elizabeth national parks, see greatlakessafaris.com. Latitude 0 Degrees in Kampala costs from $205 for two nights, see benchafrica.com.

Visit

Cafe Kibale is located beside the chimp trekking entry point at Kibale National Park; see ugandalodges.com/cafe-kibale. Gorilla Conservation Coffee’s coffee safari includes a meeting with community farmers. Its café in Entebbe is open for breakfast and lunch; see gorillaconservationcoffee.org. Fairtrade Bwindi coffee can be bought in Australia from Hilda, see hilda.com.au.

The writer was a guest of the Uganda Wildlife Authority, see ugandawildlife.org.