Ruhondeza, the gorilla that lives on in the hearts and minds of the Bwindi community

The Bwindi Impenetrable Forest is a national park in Uganda, an Important Bird & Biodiversity Area, and an Eastern Afromontane Key Biodiversity Area. The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, through a small grant facilitated by BirdLife International, supports Conservation Through Public Health in their effort to reduce human-gorilla conflicts in and around the park, and avoid the transmission of diseases. This story describes how a potential drama turned into a unique friendship between local people and a legendary animal…

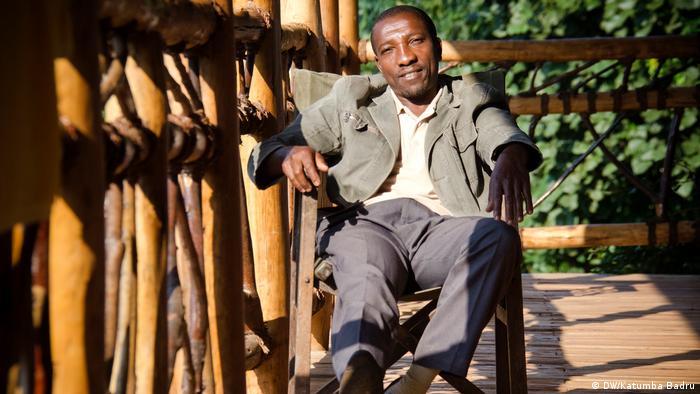

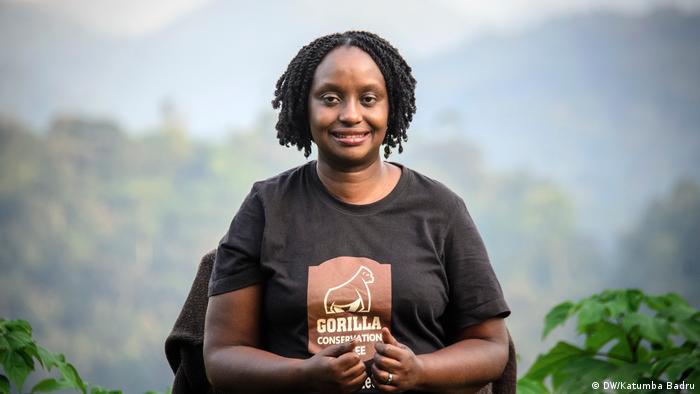

By Dr. Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka – Founder and CEO, Conservation Through Public Health (CTPH)

I have been working with mountain gorillas since 1994, when there were only two gorilla groups called Mubare and Katendegyere, habituated for tourism at Bwindi Impenetrable National Park. Now 25 years later, there are 17 gorilla groups habituated for tourism. Mubare gorilla group was headed by the silverback Ruhondeza, given that name because he liked “sleeping a lot”. Though Ruhondeza was smaller than the other silverbacks, he had the largest number of adult female gorillas to himself and was calmer than the Katendegyere gorilla group and therefore easier to habituate.

Katendegyere gorilla group eventually reduced in size, because there were too many males and only one female, and two years later the lead silverback, Mugurusi, meaning “old man” and named because he was very old when habituation began, eventually died of heart and kidney failure. I was called to check on Mugurusi when he could no longer keep up with the group and did a post-mortem on him a few days later. Fortunately, he did not have an infectious disease, however, a few months later his group developed scabies, a highly contagious skin disease more commonly known in animals as sarcoptic mange. This resulted in the death of the infant and sickness in the rest of the gorillas that only recovered after we gave Ivermectin anti parasitic treatments. The scabies was ultimately traced to people living around the national park who have inadequate access to basic health and other social services.

Kanyonyi, son of Ruhondeza © CTPH

In 2012, Ruhondeza also became too old, and he eventually could not keep up with the rest of his group. The Mubare gorilla group left him in search of food and he decided to settle outside the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in community land. When the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) park management called Conservation Through Public Health (CTPH) to look into the possibility of translocating Ruhondeza back to the safety of the forest, we checked on him and saw that he was really settled and even if we moved him back, he would likely return to community land. We spoke to our Village Health and Conservation Teams (VHCTs), volunteers who liaise between CTPH and their community, about tolerating Ruhondeza in the village – particularly since his calm and accommodating nature had enabled gorilla tourism to begin in 1993, changing the lives and future for many people in the Bwindi community for ever. In the meeting the VHCTs assured us that even when their own elderly become very weak, they look after them, so why should this not apply to Ruhondeza as well?.

This resulted in Ruhondeza being accepted in the Bwindi community where they tolerated him eating banana plants or the occasional coffee berry. When the fateful day came and Ruhondeza was laid to rest, the Bwindi community members all came to pay their last respects to a legend. To this day he is remembered through the Ruhondeza village walk and other community experiences and also through his son, Kanyonyi, who took over the Mubare Gorilla Group after he died. CTPH named the first blend of our Gorilla Conservation Coffee after him.

Ruhondeza truly signifies how far conservation efforts have paid off in Bwindi, and that true friendship between people and wild animals is, indeed, possible.

Watch Dr. Gladys Kalema Zikusoka talk more about how CTPH is working with local farmers to reduce threats to Endangered mountain gorillas around Bwindi Impenetrable National Park KBA

BirdLife International runs the Regional Implementation Team (RIT) for the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) investment in the Eastern Afromontane Hotspot (2012 -2019). See the interactive map of all projects implemented under the CEPF Eastern Afromontane Hotspot programme here.

The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the European Union, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan and the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. More information on the CEPF can be found at www.cepf.net.