He told her that Ruhondeza, the 48-year old Silverback leader of the first gorilla group to be habituated for tourism, was spotted alone in a community garden outside the forest. Gorillas that stray into villages are susceptible to human diseases and may destroy cultivated crops.

The warden asked if she would oversee the effort to move the older ape back into the park.

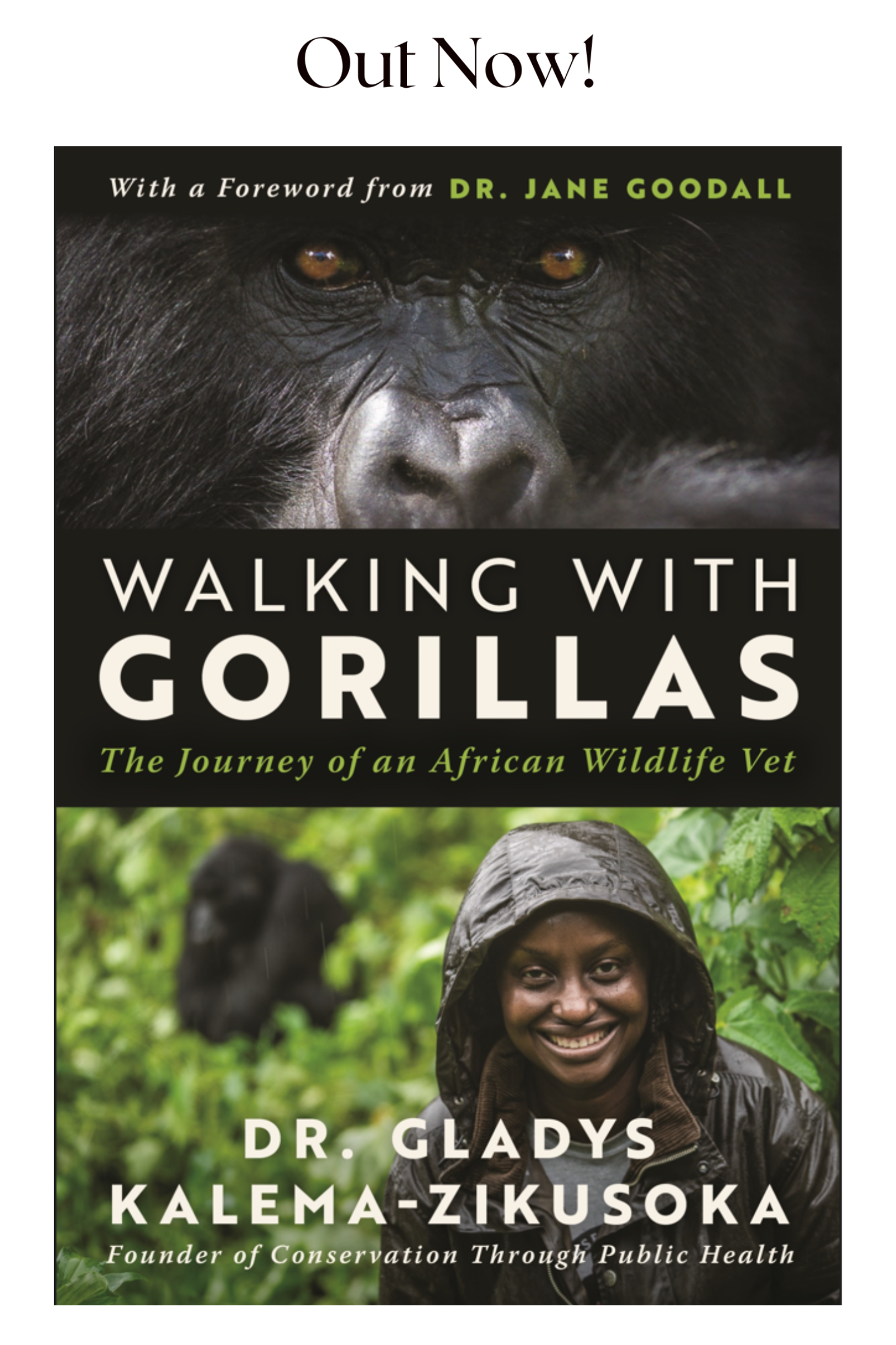

Kalema-Zikusoka was more than eager and more than qualified to save the gorilla. She won the 2022 Edinburgh Medal acknowledging her significant contribution to the understanding and well-being of humanity. In 2021, she was selected as a United Nations Champion of the Earth, and since 2017, a National Geographic Explorer.

Veterinarian Superstar

Kalema-Zikusoka and her team rushed to the scene. Carrying darting gear to tranquilize the ape, they hiked across the hilly farmland for 45 minutes until they found him hiding behind a bush, chewing banana leaves.

“He appeared calm, safer in this community of humans than in his forest home.”

“He appeared calm, safer in this community of humans than in his forest home,” Kalema-Zikusoka writes in her memoir, “Walking with Gorillas: The Journey of an African Wildlife Vet.” He had only days left to live in his fragile state, but she feared returning him to the forest would make him easy prey to territorial silverbacks.

Uganda’s most famous eco-hero you may have never heard of, Dr. Gladys, as she is known locally, is to Bwindi what Dian Fossey, Jane Goodall and Biruté Galdikas were to primates in Rwanda, Tanzania and Borneo, respectively.

Her story has attracted more attention as we approach September 24, International Gorilla Day.

She has been featured on numerous wildlife documentaries, such as “Gladys, the African Vet.” I read her memoir last May, before leaving on my third trip to Bwindi to trek for gorillas and explore the cultural scene, shop for crafts, take a traditional dance class and go on nature walks to support the local economy.

Inspired by Goodall and Galdikas

While studying at the Royal Veterinary College, University of London, Kalema-Zikusoka attended lectures by Goodall and Galdikas, later writing that the two women “inspired and encouraged me to follow my dreams.” In the foreword to Kalema-Zikusoka’s book, Goodall noted that both had a childhood passion for animals and supportive mothers. Goodall also honors Kalema-Zikusoka for overcoming personal and professional hurdles to protect endangered species.

Born in 1970, the youngest of six children, Kalema-Zikusoka grew up during General Idi Amin’s murderous regime. Her family home was filled with pets to try to assuage the grim times.

In 1972, soldiers abducted and killed her father, William Wilberforce Kalema, who had served as a senior cabinet minister in Uganda’s first parliament after the country achieved independence from the British in 1962. “I have always seen my career as a way to continue his legacy, protecting the precious wealth and heritage of Uganda,” she writes.

At 12, she decided to become a vet. While volunteering at the Wildlife Club of Uganda in 1987, a park warden confirmed that mountain gorillas were found to be living in what was then the Bwindi Forest Reserve, a 128-square-mile rainforest about twice the size of Washington, D.C. One of the most biodiverse forests in East Africa, it contains an estimated 324 species of trees, at least 120 species of mammals and 350 documented species of birds.

“You can’t address animal health and the environment without attending to human health.”

Bwindi’s evidence as the world’s second mountain gorilla habitat hastened its designation as a National Park in 1991 and a UNESCO Natural World Heritage Site in 1994.

In 1996, six months into her job setting up a veterinary unit with the Uganda national parks and becoming the first Ugandan wildlife vet, at age 26, Kalema-Zikusoka experienced a breakthrough moment.

While treating a gorilla family infested with scabies from exposure to human sewage and dirty clothing outside the park, she realized, “You can’t address animal health and the environment without attending to human health.”

Indeed, poaching, habitat loss, deforestation and disease had threatened to wipe out the Bwindi mountain gorilla population in the late 1990s. Estimates of their population fell to 300, low enough that the International Union for Conservation of Nature classified the subspecies “critically endangered.”

Kalema-Zikusoka believed a “One Health” approach was necessary to protect the gorillas by improving the health of the local community and environment. To that end, she founded the nonprofit Conservation Through Public Health in September 2003 and appointed her husband, Lawrence, as treasurer. He was a Ugandan telecoms expert she met in graduate school in North Carolina and donated the first $100 to the organization.

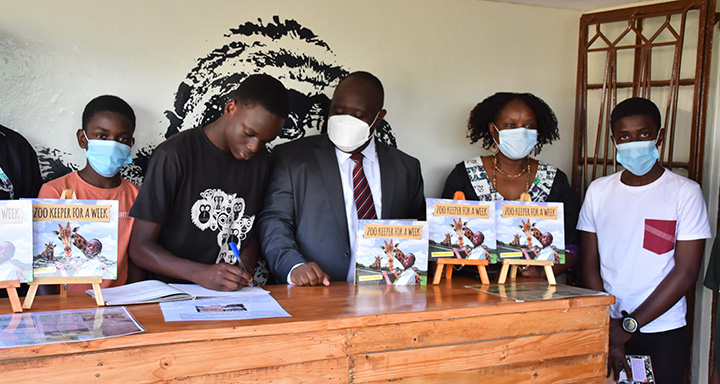

On a Zoom call from her home in Entebbe, Uganda, which she shares with Zikusoka and their two teenaged sons, she used the 20th anniversary of the nonprofit to consider its accomplishments and remaining goals.

20 Years of Progress

“At the beginning, everyone thought it was weird,” she recalled, “One Health was a relatively unknown concept when I started advocating for, and implementing, an integrated approach to conservation and health.” Donors at the time focused on either conservation or health. Not both.

Their skepticism ignited her determination. She allied herself to the residents living alongside the park, introducing Village Health and Conservation Teams to administer public health and counsel households on sanitation and hygiene.

She formed the group, Human and Gorilla Conflict Volunteers, affectionately referred to as HUGOs, to herd stray gorilla groups back into the parks. She initiated a treatment program against tuberculosis and established a community based-family planning program that encourages population management.

When Kalema-Zikusoka and her team tracked down Ruhondeza, the mischievous gorilla, and concluded he was too frail to return to the forest, she took her concerns to the Village Health and Conservation Team. She reminded the team that the silverback’s gentle nature helped his gorilla group, the Mubare, to be the first to habituate to the presence of humans in Bwindi, launching gorilla tourism there in 1993.

A Hero’s Funeral

Thanks to him, their lives and futures had improved. When their own elders grew old, didn’t they take care of them? They agreed to allow the declining ape live out his remaining days in their fields. When he died, more than 100 community members gave him a hero’s funeral.

“The kindness and willingness to tolerate Ruhondeza, signified the extent to which conservation efforts had improved in Bwindi,” Kalema-Zikusoka wrote. “Genuine friendship between people and wild animals was indeed possible.”

I trekked the legendary Mubare group in January 2020. After Ruhondeza’s death, his 17-year-old silverback son, Kanyonyi, who Kalema-Zikusoka had known since he was a baby in her early years as a vet, resumed the leadership of the family. He cut a charismatic figure and was known to “deliberately set out to frighten tourists to see their reaction — his idea of humor,” she said.

A New Leader for the Clan

Just five years into his role, Kanyonyi developed an infection after falling off a tree. While being treated with antibiotics, he got into a fight with a competing silverback and died from his wounds in 2017.

Maraya took control of the group and remains their silverback leader today. The stories behind these gorilla groups become narratives, as compelling as human family histories.

COVID-19 closed the park closed for six months in 2020 — a serious blow to Uganda. Tourism and travel account for 7.7% of the country’s economy and more than 60% of the budget of the Ugandan Wildlife Authority, which helps conserve other, less-visited parks, Kalema-Zikusoka said. Travel and tourism employ about 700,000 jobs in Uganda, which has a work force of 18 million.

Poaching Rose as Tourism Fell

“Poaching bush pigs and duikers, a small antelope, for subsistence increased drastically when tourism disappeared,” Kalema-Zikusoka said. Without the daily activities of tourism, hunters felt comfortable entering the park and setting traps, which can maim and kill gorillas. In June, a poacher startled the leader of a gorilla group, causing it to roar in his family’s defense. The illegal hunter lunged at the silverback with a spear, killing it.

Greater security and protective safeguards were implemented for the gorillas. “My team never rested,” recalled the vet. Considered essential workers, they trained rangers, gorilla guardians and village health and conservation teams on mask wearing, social distancing and detecting COVID in gorillas.

They tested the park’s staff and analyzed gorillas’ feces. “I told my team when the pandemic ends, we’re all going to take a month off,” Kalema-Zikusoka said. “It’s never really ended.”

Sgt. Head Guide Augustine Muhangi led my “habituation experience,” where guests spend four hours observing a gorilla group that is undergoing the two-year process of adjusting to the presence of humans. He is 45 years old, grew up in Higabiro Village next to the park and has worked for the Uganda Wildlife Authority for 20 years.

Benefits of Tourism

He still lives in Higabiro Village with his wife, a schoolteacher, and their three children. “Gorilla tourism has improved my village,” he said by email, listing improvements in education, infrastructure and health care. During COVID, he wrote, “gorilla monitoring and protection intensified, and we worked day and night to ensure 100% protection of the mountain gorillas from poachers and COVID-19.” There is no evidence that any of Bwindi’s mountain gorillas caught the virus.

“Gorilla tourism has improved my village.”

COVID-19 revealed the Bwindi community’s dependency on tourism. “We discovered we needed other ways to support the people living next to the park,” Kalema-Zikusoka explained. She wasted no time. Conservation Through Public Health ‘s Ready to Grow Gardens program supplied low-maintenance seedlings, harvestable within one to four months, to over 1,500 food-insecure households, prioritizing residents most likely to turn to poaching out of desperation.

In 2015, Kalema-Zikusoka had created a global, for-profit company, called “Gorilla Conservation Coffee” in response to the low prices farmers received for their beans. The award-winning enterprise pays a premium price to over 500 coffee growers, 120 of whom are women who live next to the national park. Enterprises such as this can help sustain the Bwindi community during low tourist turnouts, she believes.

The Face of Conservation Coffee

A portion of coffee sales go toward saving mountain gorillas. The image of Kanyonyi, the Mubare gorilla family’s lead silverback , remains on the brand, though he died in 2017. Kalema-Zikusoka explains: “His individual story helps tell the larger story about how helping communities that share a habitat with critically endangered gorillas can prevent them from becoming extinct.”

The last census, in 2018, revealed a rise to about 459 mountain gorillas in Bwindi; adding 604 in the Virunga National Park brings the total to 1,063. That year, the IUCN reclassified the mountain gorilla to “endangered,” making it the only gorilla sub-species whose population is growing. Kalema-Zikusoka estimates today’s Bwindi count at about 500, with 24 habituated groups.

“I’m very excited that since I first started working, the numbers have almost doubled,” she said.

And so it seems certain, that walking with gorillas and caring for them is key to helping the people who live alongside them.

Giannella M. Garrett is a writer/photographer who lives in New York City and writes about travel, dance and culture. Her stories have been published in National Geographic, the Washington Post and Conde Nast Traveler.

Book Review

Book Review

Dr. Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka on Walking With Gorillas

Dr. Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka on Walking With Gorillas Dr. Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka

Dr. Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka