SOURCE: BBC SOUNDS

Listen here

Listen here

Growing human populations in communities neighbouring protected areas have continued to become a major threat to the rising number of wildlife populations across Uganda. The continued habitat loss on the side of protected areas frustrate wildlife conservation efforts.

Human activities such as agriculture and industrialisation have forced hundreds of animal species into migration and facilitated human-wildlife conflict because activities exert more pressure on natural resources, which serve as natural habitats for animals.

In the past, people living around Queen Elizabeth National Park and Bwindi Impenetrable National Park would go into the parks for poaching and timber cutting as sources of food and livelihood.

These daily struggles caused mayhem because many members of the public lost their lives after they were killed by law enforcement teams and animals. In Rubirizi district, a number of family heads died guarding their crops against elephant raids

“Most of us are widows because our husbands were shot dead by rangers. They were found hunting in the park. Elephants destroyed our gardens and we felt like killing them in order to compensate ourselves with ivory. But we were aware that this was illegal,” Birungi Mwanje, a member of Kataara Women’s Poverty Alleviation Group (KWPAG), a group running projects that minimise environmental impacts on Queen Elizabeth National Park shares.

Coffee growing

To address this conservation challenge, communities in south western Uganda, have been organised into Arabica coffee growing and value addition groups. The two strands of growing and value addition have proven to be alternative sources of livelihood.

According to Moses Agaba, the group coordinator of KWPAG, women have since actively participated in growing of coffee and value addition.

“Most of these are widows whose husbands died in the park. They used to sell meat obtained from the park as a source of livelihood. Today, they are now busy processing coffee and they are earning a living. A woman who is busy roasting coffee cannot send her son to the park for meat,” says Agaba.

The group known as Kataara Women’s Roasted Coffee Beans, collects red coffee berries from their own gardens and out growers, process it into roasted berries or powder and sell it to tourists or hotels, where they get more yields.

“From out growers, we buy one basin of red coffee at Shs2,000 and after processing it, a basin goes for up to Shs 374,429 and to us, this is a profitable business. We cannot go back to the park,” women coffee farmers say.

During the peak season, the group fetches up to Shs2 to 3 million per month, whereas during off season, they get Shs600,000-Shs800,000. Immaculate Nyangoma Tumwebaze, the group chairperson, says they chose coffee growing after they found out that coffee cannot be eaten by elephants. Aside from coffee farming, do they do other activities such as turning elephant dung into paper and art objects, which they sell to earn money. Coffee growing also helps the residents protect their soil from erosion

Supporting community tourism

When tourists visit the Kicwamba community, where KWPAG is located, they support community tourism by visiting coffee gardens, processing centres, where they pay to see value addition activities and also end up supporting different interventions that protect the park.

In Rubirizi District, coffee contributes 68-70 percent to the economy, according to Habib Kaparaga, the district secretary for finance and administration. Areas engaged in coffee growing include Kicwamba, Katerera, Ryeru, Kirugu and Kyabakara.

Bwindi Impenetrable Forest National Park, where 1,063 mountain gorillas live today, is surrounded by isolated and impoverished communities. In the past, due to their close proximity both inside and outside the national park, preventable infectious diseases would spread between humans, gorillas and livestock.

This along with habitat encroachment, poaching and economic instability threatened the existence of the mountain gorillas, until Dr Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka, the first Wildlife Veterinary Officer of the Uganda Wildlife Authority Conservation Through Public Health (CTPH) came and established Gorilla Conservation Coffee as a social enterprise for neighbouring communities.

CTPH promotes biodiversity conservation by enabling people, gorillas and other wildlife to coexist through improving their health and livelihoods in and around protected areas and wildlife rich habitats.

Need for livelihood

Dr Zikusoka discovered that coffee farmers in Kanungu District were not being given a fair price for their coffee and were struggling to survive, forcing them into national parks to meet their basic family needs, specifically food and fuel wood.

Gorilla Conservation Coffee pays a premium of Shs1,872 per kilogramme, above the market price, according to Edward Sekandi, the CTPH operations manager.

“These are mainly former poachers, now reformed. They are converted into coffee growing. It is an intensive, engaging and profitable activity that they no longer want to go back to the park,” says Sekandi.

GCC prevents residents from practicing deforestation for charcoal and rallies them into shade tree planting in their coffee gardens in order to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

Sekandi says farmers are encouraged to use organic manure in their coffee gardens instead of artificial inputs, which he says spoil the soil structure.

Reformed poachers, who are now great farmers are supported through training in sustainable coffee farming and processing. This helps them to improve the coffee quality, increase production yield and protect the endangered gorillas and their habitat.

“When you are tracking gorillas, you tour coffee farms. We buy coffee from farmers and sell it to traders, roasters and retailers and the donations from every bag sold, goes to the work of CTPH,” says Dr Zikusoka.

Markets

The coffee is 100 percent premium Arabica, which is selectively harvested for only red ripe cherries, handpicked, wet processed and dried under shade. This coffee is tested for quality at every level. The coffee is roasted and packed to quality standards.

Each cup has a unique aroma with hints of caramel, butter notes and almond, with a citrus taste and a sweet finish. The group’s first blend is named after Kanyonyi, the former lead silverback of the Mubare gorilla group, located in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park.

The coffee is majorly sold in the US, Canada, UK, New Zealand, France and South Africa. GCC makes a special effort to support women coffee farmers, helping to provide opportunities for economic empowerment, disrupt male financial dominance and break and stereotypes.

As a black African woman in a space often dominated by white, western males, the path to becoming a conservation leader didn’t always seem open to Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka.

“I remember a warden came to talk to us at wildlife club [at school] about mountain gorillas, which had just been discovered in Uganda and were being habituated. The people involved were white American researchers,” she says.

Kalema-Zikusoka grew up in Uganda’s capital, Kampala, and by 17 was running the wildlife club at Kibuli secondary school in Entebbe, 25 miles (40km) to the south. After graduating from the University of London’s Royal Veterinary College in 1996, she established the Uganda Wildlife Authority’s first veterinary department and became the country’s first wildlife vet.

“I wasn’t sure if this job existed for me,” she recalls. “I didn’t know any wildlife vets in Uganda. When Idi Amin came into power [in 1971], he chased away the British, the Indians and made life very difficult. The people who kept the wildlife going were Africans, but it was a struggle.” Kalema-Zikusoka’s father, who was a minister in the previous government, was one of Amin’s first victims, killed when she was two years old.

When Kalema-Zikusoka became the country’s first wildlife vet it was all the more unusual because she was a woman. “Being a wildlife vet was seen as a very unusual job for a woman. When I started working, there were no female rangers. I was the only woman going out in to the field. People looked at me very strangely.”

Since then, Kalema-Zikusoka has gone on to found the wildlife charity Conservation Through Public Health (CTPH), the Gorilla Conservation Coffee social enterprise, is vice-president of the African Primatological Society and sits on the leadership council of Women for the Environment Africa.

“There are more Africans involved in conservation than 20 years ago,” she says. “There are still very few women, but it’s better than it used to be. What’s lacking is African leadership. Very few Africans are leading these efforts. We founded the African Primatological Society because of that. I was being invited to conferences to give keynote speeches about primates in Africa and only 10% of people there were from Africa. We had to change that.”

Kalema-Zikusoka is leading on a number of fronts, at home and in the international arena. She is a National Geographic Explorer, a 2021 United Nations Champion of the Earth and a member of the World Health Organization special advisory group for the origin of novel pathogens (WHO SAGO).

There needs to be a homegrown movement of African conservationists and leaders to prevent species declining

“African leaders are better able to meet the needs of the wildlife and people because we have a greater understanding,” she says. “Our relatives had to deal with human-wildlife conflict, or some people’s grandparents were poachers, so we understand the situation better. There needs to be a homegrown movement of African conservationists and leaders to prevent species declining.”

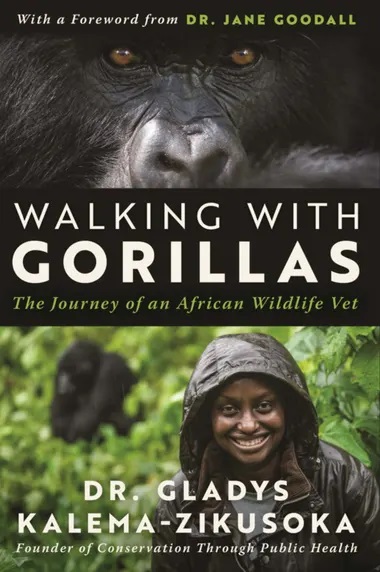

Many charities have snappier names than Conservation Through Public Health, but few “do what it says on the tin”, says Kalema-Zikusoka, whose pragmatic strategy is to protect gorillas and other wildlife by prioritising human health. She first met a mountain gorilla in Bwindi, western Uganda, in 1994, just one of the extraordinary moments in her life recounted in a new memoir, Walking With Gorillas: The Journey of an African Wildlife Vet. “I felt a strong connection,” she says. “I met just one silverback, Kacupira. I also felt they’re so vulnerable, so few in number. I felt we needed to do something to make sure they didn’t go extinct.”

In the 1970s, it was feared the world’s largest primate – found only in the Virunga Mountains that border the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda and Uganda and in Bwindi Impenetrable national park – would go extinct. But their numbers have been steadily rising, thanks to conservation efforts. The last census, in 2018, counted 1,063. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) updated their status from critically endangered to endangered.

“Humans are so closely related to gorillas and chimps, and we can make each other sick,” says Kalema-Zikusoka. “I realised people around the park had very little healthcare – many lived 20 miles from the nearest health centre. Some diseases are preventable with good hygiene, like tuberculosis, scabies … I wanted to set up an NGO that improves the health of the people, because it was difficult to keep gorillas healthy if their human neighbours weren’t healthy and hygienic.”

Tackling poverty is also central to the CTPH mission. “It’s core to protecting wildlife. As long as people are poor and don’t have food, they’re going to want to enter the forest to poach. We found this out during Covid – poaching really increased during the pandemic when there were no tourists.

“After a poacher killed Rafiki, the lead silverback in the Nkuringo group in 2020, we felt we needed to provide fast-growing seedlings to vulnerable people for food – pumpkins, kale, cabbage, beans … Once you give them something to eat, they’re less likely to enter the forest. So food security became another component of our whole model.”

Conservationists face many challenges to stop wildlife disappearing in many parts of Africa. “The biggest issue is habitat loss, which we need to deal with by promoting family planning around protected areas,” says Kalema-Zikusoka. “People were having 10 kids per family on average around Bwindi. By implementing family planning, you reduce poverty and disease. Women have more control over their bodies. And it’s very helpful for wildlife because there’s less need to enter the park to poach. Family planning is an issue all conservation NGOs need to take up.”

Kalema-Zikusoka divides her time between Entebbe, where she lives with her husband and two sons, and Bwindi Impenetrable Forest. Despite being chief executive of CTPH, she still spends much of her time out in the field with the gorillas and local communities. “I’m always there,” she says. “That’s what gives me energy. I’m a very practical hands-on person.”

Walking With Gorillas: The Journey of an African Wildlife Vet by Dr Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka is out now.

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield on Twitter for all the latest news and features

Thanks for joining us today from Uganda. For decades, the Guardian has amplified voices, studies, scientists and data that point towards irrevocable and catastrophic climate breakdown.

Our reporting has galvanised action, pushed policymakers, and encouraged innovators to seek solutions, even as the crisis deepens. For a world facing an existential threat, this is service – rigorous, provocative and tireless – that we cannot do without. Will you invest in the Guardian today? Think of it as an offset, only one that works.

Unlike many others, we have no billionaire owner, meaning we can fearlessly chase the truth and report it with integrity. We will continue to work with trademark determination and passion to bring you journalism that’s always free from commercial or political interference. No one edits our editor or diverts our attention from what’s most important.

With your support, we’ll continue to keep Guardian journalism open and free for everyone to read. When access to information is made equal, greater numbers of people can understand global events and their impact on people and communities. Together, we can demand better from the powerful and fight for democracy.

Whether you give a little or a lot, your funding will power our reporting for the years to come. If you can, please support us on a monthly basis from just £2. It takes less than a minute to set up, and you can rest assured that you’re making a big impact every single month in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

***

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions publication, and we are working to reduce our carbon emissions where possible. Emissions generated by the movements of our staff and contributors are carbon offset through our parent company, Intrepid. You can visit our sustainability page and read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information. While we take our commitment to people and planet seriously, we acknowledge that we still have plenty of work to do, and we welcome all feedback and suggestions from our readers. You can contact us anytime at [email protected]. Please allow up to one week for a response.

Countless natural disasters made worse from climate change and the degradation of our natural world feel like a steady drumbeat in the news. It’s hard not to feel discouraged, especially when we hear about the enormous amount of species that have gone extinct due to climate change and human activity. But there is hope.

This week’s edition of the Joy Beat celebrates the hard work and dedication of a world-class conservationist and wildlife veterinarian: Dr. Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka. She’s the founder and CEO of the grassroots non-governmental organization Conservation Through Public Health, and her new memoir dives into her career caring for Uganda’s mountain gorillas. She joined GBH’s All Things Considered host Arun Rath.

Arun Rath: First off, tell us about how you first got involved in conservation efforts in Uganda. I believe you started quite young, right?

Dr. Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka: Yes. I first got involved in conservation efforts when I revived a wildlife club at my high school in Uganda. I was very excited to go to the national parks. But when I saw that there was very little wildlife because it had been culled during the President Idi Amin era, I thought that I should become a veterinarian who works with wildlife.

I’d grown up with so many pets at home, and I really wanted to be a vet by the age of two. But by the age of 18, I felt like I wanted to be a vet that works with wildlife. Then, I got an opportunity to work with captive chimpanzees, and then I also got to work with chimpanzees in the wild and, finally, with mountain gorillas in the national park, one year after gorilla tourism had just begun. And I became Uganda’s first wildlife vet.

Rath: Tell us a bit more about your first encounter with gorillas and how you came to become enamored with these animals.

Kalema-Zikusoka: My first encounter with gorillas was really exciting. First of all, it took me a week before I could see them because I developed a nasty cold. But once I got better, we went to visit them, and that day we only saw one gorilla. We could be within five meters of distance with him.

I looked into his eyes, and it was a really deep connection. They’re very intelligent. I felt that they were so vulnerable, and we need to do something to protect them. At that time, there were so few left in the world, and that made me feel like I wanted to be a full-time wildlife veterinarian because I felt we needed to do something to prevent them from going extinct.

Rath: It’s interesting because Uganda has such fantastic natural beauty and wildlife, but you just reminded me in this conversation that we’re talking about the post-Idi Amin period when the wildlife had not been taken care of. Talk about what the situation was and how the country had recovered in terms of the natural landscape.

Kalema-Zikusoka: During the Idi Amin era, the president himself was hunting elephants in the national parks. The national parks were supposed to be a safe haven for wildlife. The wardens tried to stop it, but eventually, they couldn’t anymore, so elephant poaching went up. Later, when the army overthrew Idi Amin, some of the soldiers also ate meat from the forests and the national parks, so a lot of numbers went down, and the elephants and rhinos were pushed to extinction.

Then, in 1987, mountain gorillas were discovered. They thought the only population was in the Virunga Mountains, but suddenly, in ‘87, after doing genetic studies, they found out that there is a second population. Having seen how Rwanda was benefiting from mountain gorilla tourism, Uganda started to habituate them, and a few years later, tourism began.

That completely transformed the situation in Uganda because gorilla tourism is now raising so much revenue that some of it was going to support the other national parks that don’t get enough tourists because they don’t have enough wildlife or it’s not easy to get to the wildlife. It really transformed the landscape.

When I first started working with gorillas, there were only two groups habituated for tourism. Now, there’s 22 groups. So at any one time, you can have almost 180 people in the park, whereas before, there were only 12 people.

It’s transformed people’s lives. Most people employed by the park are from the local communities, and we are also engaging them in our nonprofit, so it’s really transforming the whole area.

“You can’t protect the gorillas and their habitat without improving the health and well-being of the people who they share their fragile habitats with.”

Rath: My next question was going to be about how your NGO, Conservation Through Public Health, and how public health ties into wildlife conservation. But I feel like you gave us a bit of a preview on that. Talk about that some more.

Kalema-Zikusoka: Actually, one of the very first cases I had to deal with as Uganda’s first wildlife vet working for the national parks, which later became the Uganda Wildlife Authority, was a skin disease outbreak on the then-critically endangered mountain gorillas. They called me and said the gorillas are developing white, scaly skin. So I wondered what it could be, and a human doctor friend of mine told me the most common skin disease in people is scabies.

So I went with a drug called ivermectin, which is very good for any parasites. When we got there, it turned out to be scabies. The baby gorilla had sadly died, but the others recovered with treatment. Their hair started to grow back and stop scratching.

We started asking ourselves, “Where could this have come from?” The two groups habituated for tourism was spending a lot of time outside the national park because their habitat had been cut down, and they were always going out to look for banana plants. It had been cut down because of the high human population density. We found that those people were very poor and they had very little health care. When we met with them, they said they wanted to improve the situation because they don’t want to make the gorillas sick, and they wanted to be more healthy and have better well-being.

This made me realize you can’t protect the gorillas and their habitat without improving the health and well-being of the people who they share their fragile habitats with. A few years later, we founded Conservation Through Public Health.

I did research looking at tuberculosis in people, wildlife and livestock, and I understood how the public health system works in Uganda. All of this information helped us to found Conversation Through Public Health.

Rath: As I mentioned at the top, it seems like most of what we hear about wildlife and conservation is typically bad or terrible news — almost panicking. It’s nice to be able to talk to you about hopeful stories like this, about how wildlife can rebound. Can I ask you for any additional hope? Are there ways in which what you’ve accomplished in Uganda could apply in other places? Are there other ways that we could do what you’ve been able to pull off there?

Kalema-Zikusoka: Actually, we have found that as the health of the community is improving, people are not poaching as much. We show them that we care about them and their health, which is a basic human right, and not only about the wildlife and the forests. We’re very excited about that.

Tourism has also helped. Communities are much happier. I’ll say that there are other countries in Africa where the numbers of gorilla species are going down, but the mountain gorilla population has almost doubled over the past 25 years and is still growing, which is exciting.

In other countries in Africa, where there are no community benefits, there isn’t much support for communities — there’s still a lot of hunting. This particular model could really work, and it could also work in other areas with other wildlife.

I’ve actually been speaking at the Wilson Center today, and the very question they asked was like this. They said, “We would love to scale up our approach to other parts of the world.”