Source: ABC RN / By Nick Baker and Jessie Kay for Saturday Extra | August 8th, 2023

When Idi Amin launched a coup and took power of Uganda in 1971, Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka’s father was among the first victims of the brutal dictatorship that followed.

“[My father] was a senior cabinet minister in the previous government … [so] he was abducted and killed,” she tells ABC RN’s Saturday Extra.

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka was two years old at the time, and she grew up wanting to follow in her father’s footsteps — by devoting her life to helping the country develop and thrive.

On a high school visit to Uganda’s Queen Elizabeth National Park, it became clear how she could do it.

The park had very little wildlife, as much of it had disappeared over Idi Amin’s eight years in power.

During that time, both poaching and the ivory trade were encouraged, with the dictator himself hunting animals in the country’s national parks.

“I thought, ‘Why don’t I become a vet who can bring Uganda’s wildlife back to its former glory’,” Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says.

Changing the attitude to conservation

After high school, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka won a scholarship to study at the University of London Royal Veterinary College.

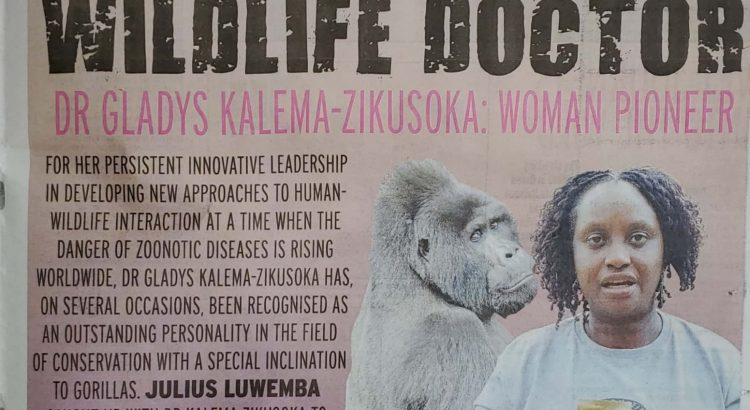

When she returned to Uganda, she convinced the government to appoint her as the country’s first wildlife veterinarian.

“[But] the attitude towards conservation back then was that animals shouldn’t be touched. They should just be left to natural selection,” she says.

“People looked at me rather strangely when I said we have to treat [injured or sick] animals.”

A key focus for Dr Kalema-Zikusoka was the mountain gorillas of Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, which represent around half of the world’s population of these great apes.

At the time, they numbered just 300 in the park.

And their biggest problem — by far — was humans.

When humans and animals interact

For the Bwindi gorillas, there is a litany of threats from humans.

Habitat destruction and poachers are among these, but what’s less recognised is the health impact of having humans living in very close proximity.

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says humans and gorillas are “always mixing” as there are communities located right on the edge of the park.

And just as humans can pass on illness to other humans, they can also pass on illness to gorillas.

“We share over 98 per cent of our genetic material [with the gorillas] … We’re closely related and we can easily make each other sick,” she says.

An unusual case of scabies

One of the first jobs that Dr Kalema-Zikusoka undertook as government vet was looking into a skin condition affecting the Bwindi gorillas.

The gorillas had rashes and were insatiably itchy — symptoms similar to scabies.

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says there are occasional scabies outbreaks in some less-developed communities in Uganda.

“This gorilla group was spending a lot of time outside the park. So they probably came across dirty clothing … and that’s how they got it.”

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka was able to treat the gorillas with medicine, but one baby gorilla died from the skin condition.

Living side by side

The scabies case, particularly the baby gorilla’s death, was “a big eye-opener” for Dr Kalema-Zikusoka.

“I realised you couldn’t really keep the gorillas healthy without improving the health of their human neighbours.”

But at the time, healthcare options in the communities around the park were dismal.

“[People near the park] had very limited access to good healthcare … the nearest health centre was around 20 miles [32km] away,” she says.

“If someone fell sick, they had to carry them on a stretcher to the health centre.”

So in 2003, she co-founded a non-profit organisation called Conservation Through Public Health, which focuses on the interdependence of human health and that of wildlife, specifically gorillas.

Her approach to conservation is known as “One Health”, which is about “addressing things holistically”.

As part of the work, “teams spread good health and hygiene [messages] and good conservation attitudes and practices”, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says.

She says the approach is working.

After a few years of the holistic conservation practice, human and animal health outcomes changed.

“We found that as people were falling sick less often, gorillas were falling sick less often,” she says.

A 2018 count found that the Bwindi gorilla population had increased by more than 150 — to 459 in total — which moved them from “critically endangered” to “endangered”.

For her work, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka has received praise from the likes of conservation royalty Jane Goodall, who she first crossed paths with in 1993.

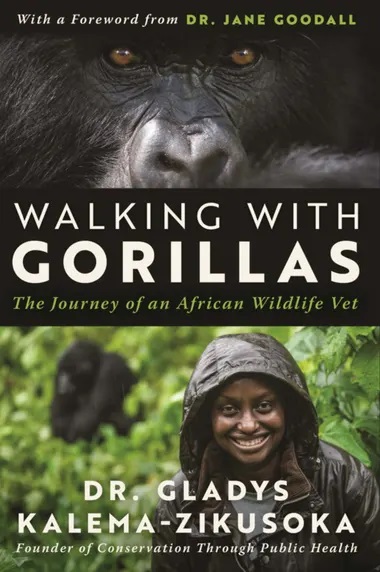

Dr Goodall supplied the foreword to Dr Kalema-Zikusoka’s new memoir, Walking with Gorillas: The Journey of an African Wildlife Vet.

“She has made a huge difference to conservation in Uganda, and she is an inspiring example,” Dr Goodall writes.

COVID-19 and gorillas

Gorilla tourism has been part of Uganda for three decades — and it’s brought dollars and development to communities near the park.

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka wants outsiders to come and safely meet the great apes, but it’s not without risk.

“Tourists can bring a fatal flu,” Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says.

Researchers have documented cases where humans have passed on respiratory viruses to gorillas, and while these are often mild, they are sometimes deadly.

So when COVID-19 hit, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka and her team swung into action to further protect the gorillas.

Elsewhere in the world, at San Diego Zoo Safari Park and Prague Zoo a number of gorillas tested positive for COVID-19 after catching the virus from humans.

“During the pandemic, we advocated to the government that everybody should wear masks when they come close to the gorillas, whether it’s the park staff or the tourists or the local community members,” Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says.

“And that really worked. The gorillas did not pick up COVID from people.”

She says the pandemic has made even more people understand the connection between animal and human health, and that “diseases can jump back and forth” between the two.

And while there is still work to be done to improve human and animal health in Uganda, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says the attitude towards the country’s wildlife — especially the gorillas — has changed.

“The communities really see gorillas as their future,” she says.