Poor communities in Bwindi national park have long depended on what the forest can provide. But with gorillas under threat, coffee now offers a more sustainable living.

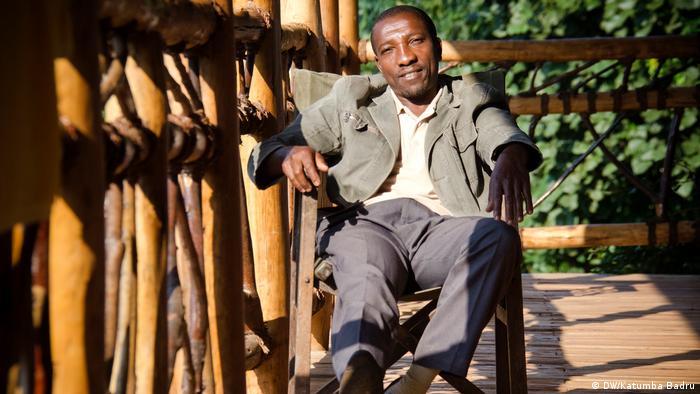

Robert Byarugaba, now 45, began poaching with his father in Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable Forest at just eight years old.

“My dad would force me to follow him to go in the park because I was his only son,” Byarugaba says. “We poached and hunted from Monday to Sunday. Every day we would be in the forest.”

The father and son weren’t the only ones, there were many hunters who combed the forest for bushpigs, antelopes, goats, and sometimes gorillas. The great apes might be killed to feed local families, or their meat and body parts could fetch high sums on the market for bush meat or traditional medicine.

Read more: Dian Fossey: Gorilla researcher in the mist

Uganda is home to almost half of the world’s estimated 1,000 surviving mountain gorillas. In 1991, when the primates’ population fell to an estimated 300 animals, the Ugandan government made Bwindi a national park. That meant increased protection and regulation of access to the park. But many poachers continued to hunt all the same because their livelihoods depended on it.

Read more: Gorilla population in Africa rises

After five years, Byarugaba gave up poaching and began to grow coffee, but he couldn’t sell enough to make a living and supplemented his income taking tourists bird spotting in the forest.

Since 2017, that’s changed. Thanks to the work of Gorilla Conservation Coffee, Byarugaba says he now makes a reliable living from his coffee plantation. The social enterprise advises coffee growers and buys their crop, so they don’t have to resort to pillaging the forest.

Read more: The wilderness and the war

Making coffee profitable

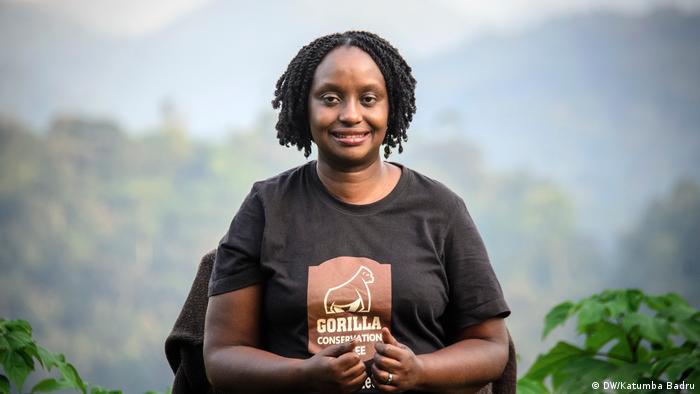

The project was started by Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka. A wildlife veterinarian, she first came to Bwindi in 1994 and was struck by the poverty blighting villagers in the national park. Later, she founded the NGO Conservation Through Public Health (CTPH) to tackle disease transmission between humans and wildlife. Tracking gorillas through the forest, she would cross coffee farms. That got her thinking.

Read more: 10 facts you probably didn’t know about great apes

Not all coffee farmers were supplementing their meagre income with legal occupations like bird spotting. “We found that some of them were poachers and were going into the forest in order to just get food to feed their families and firewood to cook, and they didn’t have enough money to buy meat,” Kalema-Zikusoka says.

Veterinarian Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka realized that to protect gorillas, people had to be lifted out of poverty

Veterinarian Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka realized that to protect gorillas, people had to be lifted out of poverty

One farmer who fitted that profile was Safari Joseph. He began growing coffee in 2007 but like Byarugaba, for many years he didn’t make enough from it to live on. He got together with others in his community to find a solution. “Our challenge was that when we started coffee growing, our coffee had no market,” he says.

“That’s when we went to Dr. Gladys and convinced her to work with us and market our coffee.” She said yes, on the condition that they stop poaching. In 2015, Kalema-Zikusoka founded Gorilla Conservation Coffee.

Today, the brand supplies shops in Uganda, Kenya, New Zealand, Canada and the United States. It currently pays the equivalent of €0.31 ($0.34) for a kilo of red coffee cherries, almost twice the regular market price. The 500 farmers benefiting from these premium prices are members of the Bwindi Coffee Growers Cooperative, to which Joseph serves as secretary.

Musiimenta Allen, 32, oversees compliance for the cooperative, making sure its members adhere to practices that protect the forest. She is also one of two women on its committee — a position she uses to ensure the voice of female coffee farmers is heard.

Since her husband died in 2014, Allen has had to support herself and her two boys from her coffee plantation. She used to depend on the forest for daily essentials like firewood, but since joining the cooperative in 2016, she can afford to buy firewood instead.

Read more: Can renewable energy save Uganda’s Rwenzori glacier?

Struggling with cash flows and pests

Despite the gorilla logo that distinguishes Allen’s coffee on supermarket shelves, neighborly relations with the endangered primates aren’t always smooth. Occasionally, they invade her farm and destroy her crops. She also wishes Gorilla Conservation Coffee could provide its farmers with loans so they could increase production. “Sometimes I want to grow more coffee but I don’t have [enough] money,” Allen says.

And Joseph is concerned that Gorilla Conservation Coffee cannot always afford to buy all the coffee from its farmers, leaving them frustrated.

Kalema-Zikusoka concedes this is a problem. Gorilla Conservation Coffee relies on donor funding to buy coffee up-front and cut out the middlemen. But that means it doesn’t always have the cash to buy as much coffee as it could sell. “Because we don’t have enough money to buy coffee from the farmers, we aren’t able to fulfil the demand,” she says.

Byarugaba would also like to see the social enterprise provide more technical support. It teaches farmers better practices, but doesn’t provide experts to evaluate their farms. “Sometimes there are pests and diseases that we don’t understand, and the coffee trees get dry,” he says.

Read more: Africa’s Green parties bet on international help

An ethical choice over the thrill of the chase

And there’s something else about Byarugaba’s life as a farmer that leaves him wanting. He misses the old days, the thrill of the chase as his dogs gained on an antelope, the sound of hunting bells, and days trekking through a forest he rarely visits nowadays.

The ripening cherries of a Bwindi coffee plant. Commanding a premium price, the crop offers viable alternative to poaching

The ripening cherries of a Bwindi coffee plant. Commanding a premium price, the crop offers viable alternative to poaching

“I like poaching, most of the things I enjoyed in my life was poaching,” Byarugaba says, looking out over Bwindi Impenetrable Forest and breaking into a chuckle. Yet, on balance, he says it’s worth the sacrifice: “With coffee farming, I can always be assured of school fees for my children.”

Bwindi’s gorilla population has now grown from fewer than 300 in 1995 to over 400 . So, as well as paying a decent living, Byarugaba feels his decision has contributed to a greater good.

“In past years, I regretted [my decision] because we could get much from the forest,” he says. “Then I started earning some money and I don’t regret anymore: this life is better than the first.”

Author: Caleb Okereke-DW.COM