SOURCE: ALL AFRICA

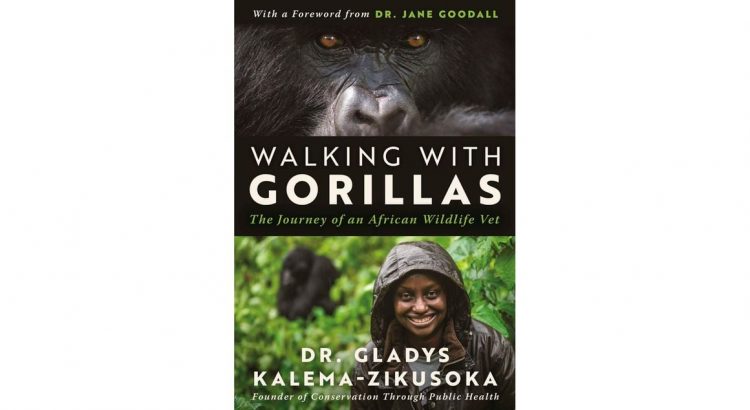

Dr. Gladys Kalema Zikusoka’s memoir, “Walking with Gorillas”, is a testament to her unwavering dedication to wildlife conservation.

Dr Kalema has made history by becoming Uganda’s first wildlife veterinarian and founder of the non-governmental organisation, Conservation Through Public Health (CTPH).

This is a globally acclaimed community programme ensuring the survival of the mountain gorillas.

Her memoir is divided into four parts, each revealing a crucial aspect of her journey towards becoming a wildlife veterinarian and founder of CTPH.

In the first section of the book, Dr. Kalema recounts how the assassination of her father influenced her decision to pursue a career in veterinary medicine.

Despite cultural beliefs that discouraged girls from studying veterinary medicine, Dr. Kalema overcame several challenges to pursue her dream. Her journey to becoming a wildlife veterinarian began with Wildlife Clubs of Uganda, where she first learned about the mountain gorillas of Bwindi.

The second part of the memoir describes Dr. Kalema’s experiences in wildlife veterinary medicine. She recounts how she tackled significant challenges in her job, such as relocating elephants and treating a mysterious skin disease affecting giraffes.

However, it was the outbreak of an unusual skin disease that threatened the lives of mountain gorillas that inspired her to start an NGO seven years later that would address human health and seek to create solutions in which human and gorilla communities can coexist in harmony.

This part of the memoir takes readers through Dr. Kalema’s decision to establish Conservation through public health as an NGO in Uganda, detailing the successes and challenges she faced in promoting understanding for the need for an integrated response to conservation and health.

One of the highlights is Dr. Kalema’s recognition as an entrepreneur and leader in her field, including serving on the boards of Uganda Wildlife Education Centre, and Uganda Wildlife Authority.

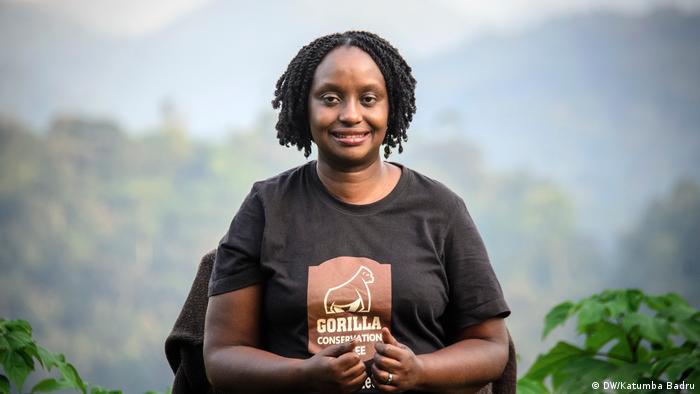

The final section of the memoir focuses on the future of conservation, offering insights on ways to support it in sustainable ways that aren’t dependent on donors. This part emphasises the importance of ecotourism and highlights the conservation and social contributions of CTPH’s social enterprise, Gorilla Conservation Coffee. The section also addresses the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on conservation efforts and wildlife populations and Dr. Kalema Zikusoka’s personal battles with the virus.

“Walking with Gorillas” highlights the critical role of wildlife conservation in our environment’s sustainability and the importance of One Health approaches.

Dr. Kalema said the government needs to put more money into conservation and tourism, adding that tourism has helped greatly in shaping the industry.

“Conservation is about being ready to get your shoes dirty and enjoy wildlife,” she said.

The US Ambassador to Uganda, Natalie Brown who was the guest of honour during the launch of the book, expressed her love for animals and congratulated Dr. Kalema upon publishing her memoir.

“It’s an engaging lesson for all and useful information on the importance of conservation and its connection to health. The US is proud of its work over the years to support efforts to preserve the environment and Uganda’s 🇬’s biodiversity for future generations,” she said.

The Chief Executive Officer of the Uganda Tourism Board, Lilly Ajarova, said the book “Walking with Gorillas” is a reflection on Dr. Kalema’s upbringing in Uganda and career as a wildlife veterinarian.

“We are very excited that we have this publication as another tool that will be able to create awareness about Uganda,” she said.

The executive director of Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA), Sam Mwandha, congratulated Dr. Kalema for writing the book, noting that it is a marketing tool for the national and for the wildlife in Uganda.

Gorillas remain the single most important item on Uganda’s tourism menu according to the Uganda Tourism Board

With conservation taking the mountain gorilla off the edge of extinction, the mantle is still left to the country to keep things from slipping back.