The BBC has revealed its list of 100 inspiring and influential women from around the world for 2023.

Among them are attorney and former US First Lady Michelle Obama, human rights lawyer Amal Clooney, Ballon d’Or-winning footballer Aitana Bonmatí, AI expert Timnit Gebru, feminist icon Gloria Steinem, Hollywood star America Ferrera and beauty mogul Huda Kattan.

In a year where extreme heat, wildfires, floods and other natural disasters have been dominating headlines, the list also highlights women who have been working to help their communities tackle climate change and take action to adjust to its impacts.

The list includes 28 Climate Pioneers, named ahead of the United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP28.

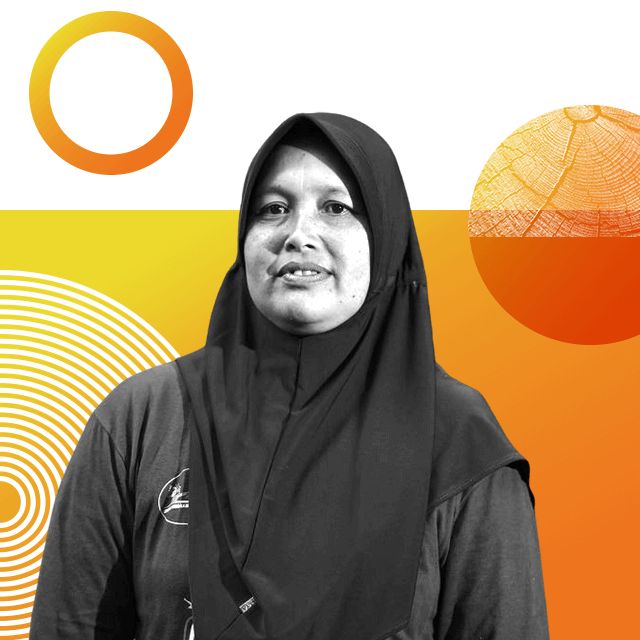

Sumini, Indonesia

Forest manager

In Indonesia’s conservative Aceh province it is unusual for women to be leaders.

When Sumini realised a major cause of floods in her village was deforestation, which also contributes towards climate change, she decided to take action and work with other women in the community.

Her group received a permit from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry allowing the community of Damaran Baru village to manage the area, all 251 hectares of forest, for 35 years

She now leads a Village Forest Management Unit (LPHK), to discourage illegal logging and hunters threatening Sumatran tigers, pangolins and other at-risk wildlife.

With rampant deforestation and wildlife poaching these days, forests should get more and more attention when it comes to how we collectively tackle the climate crisis. Keep the forest, keep the life.

Sumini

Sonia Kastner, US

Wildfire detection tech developer

This year has seen wildfires ravage some of the world’s biggest forests. With firefighters often struggling to keep up with the scale and spread of the blazes, Sonia Kastner founded an organisation to help detect them earlier.

Pano AI uses artificial intelligence technology to prepare a faster response before fires spread by scanning the landscape for signs of ignition and alerting responders, instead of relying on members of the public to call emergency services.

Kastner previously spent more than 10 years working in a variety of tech start-ups.

What gives me hope is the incredible power of human innovation. I have witnessed first hand the potential of technology and data-driven solutions to help address the worst impacts of the climate crisis.

Sonia Kastner

Dayeon Lee, South Korea

Campaigner for Kpop4Planet

Through Kpop4Planet, Dayeon Lee is rallying K-pop fans all around the world to confront the climate crisis.

Since its launch in 2021, the campaign group has asked influential people at South Korea’s biggest entertainment labels and streaming services to take climate action, and transition to renewable energy.

The group has highlighted the environmental implications of physical album waste, which prompted iconic figures in K-pop to pivot to digital albums.

Dayeon Lee is now moving beyond music, to challenge the climate pledges of luxury fashion brands, which often feature K-pop celebrities as their public face.

When standing for social justice, we never give up until we make a change. We have proved this time and again, and will continue to do so, fighting against the climate crisis.

Dayeon Lee

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka, Uganda

Veterinarian

As an award-winning Ugandan vet and conservationist, Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka works to save the country’s endangered mountain gorillas, whose habitat is being eroded by climate change.

She is founder and CEO of Conservation Through Public Health, an NGO that promotes biodiversity conservation by enabling people, gorillas and other wildlife to co-exist, while improving their health and habitat.

After three decades, she has helped increase the number of mountain gorillas from 300 to about 500, which was enough to downgrade them from critically endangered to endangered.

Kalema-Zikusoka was named a Champion of the Earth in 2021 by the United Nations Environment Programme.

What gives me hope in the climate crisis is the increasing acknowledgement that it needs to be addressed urgently. There are innovative methods to mitigate and adapt to this crisis.

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka

Leanne Cullen-Unsworth, UK

Marine scientist

Seagrass is known for its ability to store carbon and provide nurseries for fish, but some underwater habitats have been devastated.

Leanne Cullen-Unsworth is one of the founders and current CEO of Project Seagrass, the UK’s first seagrass restoration scheme at a meaningful scale.

The project makes the process easier by using a remote-control robot to plant seeds, and could create a blueprint to help other countries restore their underwater meadows.

An interdisciplinary scientist with more than 20 years of experience in marine research, Cullen-Unsworth is devoted to science-based conservation and restoration.

There is too much to do for anyone to achieve things alone, but people are working together and sharing knowledge. For my own small part, I know we can revive a vital habitat, protect it and restore it for all of the benefits it provides our planet and society.

Leanne Cullen-Unsworth

Jess Pepper, UK

Founder of Climate Café

Climate Café is a community-led space where people come together to drink, chat and act on climate change. The first one was founded by Jess Pepper in 2015, in the Scottish village of Birnam, Perthshire.

She now supports other communities to start their own spaces, linked together in a global network.

Attendees say these are safe spaces where they can share their ideas and concerns about the climate crisis.

Pepper holds a number of leadership roles within the climate sphere, is an honorary fellow of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society and a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts.

Climate action and positive change is happening in communities, often led by women and children. Seeing how connections are inspiring and informing change, building resilience whilst creating opportunity and political space for further change, gives me hope.

Jess Pepper

Matcha Phorn-in, Thailand

Campaigner for indigenous and LGBTQ+ rights

Living in Thailand on the border with Myanmar, an area which has experienced the effects of both climate change and conflict, Matcha Phorn-in has focused her work on the rights of minorities.

She founded the Sangsan Anakot Yawachon Development Project, an organisation that aims to educate and empower thousands of stateless and landless indigenous women, girls, and young members of the LGBTQ+ community.

As an ethnic minority/indigenous lesbian feminist, Matcha Phorn-in has a leading role in the movement to stop gender-based violence in the region, while also advocating for land rights and climate justice for displaced and disenfranchised people.

There can’t be sustainable climate solutions without the meaningful participation and voices from indigenous communities, LGBTQIA+, women and girls.

Matcha Phorn-in

Bayang, China

Diarist and sustainability advocate

Since 2018, Bayang has been keeping an eco-diary, monitoring local species and changes to water sources, recording the weather and observing plants.

She lives in China’s Qinghai Province, which is situated mostly on the Tibetan Plateau and is already experiencing the effects of climate change such as higher temperatures, melting glaciers and desertification.

Bayang is part of the Sanjiangyuan Women Environmentalists Network, and advocates health and sustainability in her community.

She has acquired skills in crafting eco-friendly products – including lip balm, soap and bags – to protect local water sources and inspire others to join the environmental cause.

Sophia Kianni, US

Student and social entrepreneur

After speaking to relatives in Iran, social entrepreneur Sophia Kianni realised that there was relatively little reliable information about climate change in their language, so she began translating materials into Farsi.

This soon expanded into a wider project when she founded Climate Cardinals, an international youth-led non-profit group that aims to translate climate information into every single language and make it more accessible to those who don’t speak English.

It now has 10,000 student volunteers across 80 countries. They have translated one million words of climate material into more than 100 languages.

Kianni’s aim is to help break down language barriers to the global transfer of scientific knowledge.

Young activists have built and nurtured global climate action networks, mobilised millions to protest, driven thousands of petitions against fossil fuel development, and raised millions of dollars to fund climate initiatives. The world’s challenges are too great for us to silo ourselves based on age or experience.

Sophia Kianni

Basima Abdulrahman, Iraq

Green building entrepreneur

In 2014, when the so-called Islamic State group took over huge parts of her home country, Iraq, Basima Abdulrahman was studying at university in the US.

Many Iraqi towns were destroyed as a result of fighting, but when Abdulrahman returned home after her masters in structural engineering, she saw a way of helping.

She founded KESK, Iraq’s first initiative dedicated to green building. She found that creating greener structures meant combining the latest energy-efficient technologies and materials with Iraq’s traditional building methods.

She is committed to ensuring that today’s building practices do not compromise the well-being of future generations.

I am often anxious about the climate crisis. I can’t help but wonder how anyone can find peace without being part of the solution to mitigate its risks.

Basima Abdulrahman

Marcela Fernández, Colombia

Expedition guide

Glaciers provide an essential source of freshwater for local communities, but in Colombia they are rapidly disappearing.

Founder Marcela Fernández and her colleagues at the NGO Cumbres Blancas (White Peaks) raise awareness of the issue, highlighting that of the 14 glaciers that once existed, only six are left and these are at risk.

Through scientific expeditions and by assembling a team of mountaineers, photographers, scientists, and artists, Fernández monitors changes and develops creative ways to prevent glacier loss.

With her adjacent project, “Pazabordo” (Peace on board), she also travels to areas affected by violence during Colombia’s 50-year internal armed conflict.

Glaciers have taught me to deal with grief, with absence. When you hear them you know that their loss is a damage we can’t undo, but we can still contribute and leave a mark.

Marcela Fernández

Natalia Idrisova, Tajikistan

Green energy consultant

Women living in remote parts of Tajikistan often struggle to access energy sources such as electricity or firewood. Environmental charity project co-ordinator Natalia Idrisova seeks practical environmental solutions to this energy crisis and educates women about natural resources and energy-efficient technologies and materials.

Besides training, her organisation offers energy-saving equipment, solar kitchens and pressure cookers, freeing up time for the women and supporting gender equality in the home in a climate-friendly way.

Now Idrisova is training communities on how climate change specifically affects people with disabilities and finding ways to ensure these voices are heard in political discussions.

Extreme events around the world give us the last warning that people are inseparable from nature. We cannot negligently exploit nature without serious consequences.

Natalia Idrisova

Susanne Etti, Australia

Sustainable tourism expert

One of the few climate scientists in the travel and tourism sector, Susanne Etti is passionate about leading the industry towards a more sustainable future.

Her work as the global environmental impact manager at Intrepid Travel, a small-group adventure travel business, has led the company to become the first tour operator with verified science-based carbon reduction targets.

Etti has authored an open-source guide for travel businesses wanting to decarbonise and is a key part of Tourism Declares, a voluntary community of 400 travel organisations, companies and professionals who have declared a climate emergency.

Today we are seeing more businesses recognising the importance of climate action by setting ambitious goals to reduce environmental impact, investing in renewable energy and committing to long-term emission reduction targets.

Susanne Etti

Anne Grall, France

Comedian

The Greenwashing Comedy Club is a stand-up collective that addresses environmental issues as well as feminism, poverty, disability and LGBTQ+ rights.

It was founded by stand-up comedian Anne Grall, who believes that through punchlines, it is possible to sow the seeds of change in people’s minds and even influence their habits.

In a society driven by entertainment, where concise concepts and short messages prevail, Grall believes that humour, often reliant on exaggeration and punchlines, can be an excellent medium to share ideas around climate change.

The success of the Greenwashing Comedy Club is quite heartening because it indicates that today many people are concerned about climate change, and they want to come together, laugh, and leave the show feeling ready to continue the fight!

Anne Grall

Kera Sherwood-O’Regan, New Zealand

Indigenous rights and disability advocate

A Kāi Tahu indigenous and disabled climate expert, Kera Sherwood-O’Regan is from Te Waipounamu, the South Island of New Zealand.

She is the co-founder of Activate, a social impact agency specialising in climate justice and social change.

Her practice is grounded in Māori approaches to land and ancestors, which until recently were ignored by the mainstream climate conversation.

Sherwood-O’Regan has built relationships with ministers, officials and broader civil society to highlight the effects of climate change on her communities, while advocating for greater recognition of the rights of indigenous people and people with disabilities in the climate negotiations.

We are rejecting the extractivist model, we are taking up space, we are leading with community – and it is working. I think many people now recognise that the realisation of indigenous sovereignty is the solution to the climate crisis.

Kera Sherwood-O’Regan

Sagarika Sriram, United Arab Emirates

Educator and climate adviser

Teenager Sagarika Sriram is fighting to make climate education mandatory in schools.

Using her coding skills, she set up the online platform Kids4abetterworld, designed to help educate children around the world and support them in sustainability projects in their communities.

She backs this up with online and offline environmental workshops, teaching children how they can have a positive impact on climate change.

Alongside studying for her A-levels in Dubai, Sriram is part of the children’s advisory team of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, where she champions environmental rights.

It is not time for alarm but for action, so each child is educated to live sustainably and drive the systemic changes we need to see in our world.

Sagarika Sriram

Wanjira Mathai, Kenya

Enviromental adviser

An inspiring leader for an entire continent, Wanjira Mathai has more than 20 years of experience advocating for social and environmental change.

She led the Green Belt Movement, an indigenous grassroots organisation in Kenya that empowered women through the planting of trees, established by Wanjira’s mother and winner of the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize, Wangari Maathai.

Mathai is now the managing director for Africa and Global Partnerships at the World Resources Institute, and the chair of the Wangari Maathai Foundation.

She currently serves as Africa adviser to the Bezos Earth Fund, as well as to the Clean Cooking Alliance and the European Climate Foundation.

Action is “local”. We need to support local initiatives like tree-based entrepreneurs and community-led work around restoration, renewable energy and the circular economy. Bottom-up efforts like these give me hope as they show us what is possible.

Wanjira Mathai

Neha Mankani, Pakistan

Midwife

When devastating floods hit Pakistan last year, midwife Neha Mankani travelled to affected areas to offer her skills.

Through her charity, Mama Baby Fund, Mankani and her team provided life-saving birthing kits and midwifery care to more than 15,000 flood-affected families.

Her typical practice focuses on low-resourced settings, emergency response and climate-affected communities.

Mama Baby Fund has now raised enough money to launch a boat ambulance that will transport pregnant women living in coastal communities to nearby hospitals and clinics for urgent treatment.

The work of midwives in communities facing climate-related disasters is vital. We are both first responders and climate activists, who make sure women can continue to receive the reproductive, pregnancy, and postpartum care they need, even when the situation around them is deteriorating.

Neha Mankani

Anna Huttunen, Finland

Carbon impact tech expert

As a sustainable mobility enthusiast, Anna Huttunen pushed for greener, cleaner, more efficient mobility in the Finnish city of Lahti, named the European Green Capital 2021.

She led the city’s ground-breaking personal carbon trading model – the world’s first app to allow citizens to earn credits by using environmentally friendly transportation such as cycling or public transport.

She works as climate neutral cities adviser for NetZeroCities, an organisation which helps European cities attempt to reach climate neutrality by 2030.

Huttunen aims to make others excited about sustainable mobility and is a keen advocate for cycling, which she considers the future of transport in cities.

Municipalities around the world are full of amazing people working towards enabling a more sustainable life for their citizens. Do your part, get engaged and be part of the transformation!

Anna Huttunen

Trần Gấm, Vietnam

Biogas business owner

In 2012, Trần Gấm started introducing more climate-friendly energy sources to farms in Vietnam.

The mother-of-two saw a gap in the market and started a business installing and managing biogas plants in Hanoi, later expanding the operation to three neighbouring provinces.

Her project helps farmers cut costs by turning cow and pig manure, water hyacinth and other waste into biogas – considered a far more sustainable energy source than natural gas – which can then be used as energy for cooking and running a household.

Businesses like Trần’s engage local communities and drive the political support needed for climate change mitigation.

We must live, and must live well, so I have tried to cope and protect loved ones by enhancing our health through physical exercise, eating a balanced diet, and maintaining sleep patterns. I also encourage people to live an organic lifestyle, growing their own fruits and vegetables, and advocating against using chemical pesticides on our vegetables.

Trần Gấm

Arati Kumar-Rao, India

Photographer

Working across South Asia, independent photographer, writer and National Geographic Explorer Arati Kumar-Rao documents the changing landscape caused by climate change.

She chronicles how drastically depleting groundwater, habitat destruction and land acquisition for industry devastate biodiversity and shrink common lands, displacing millions and pushing species towards extinction.

Kumar-Rao has crisscrossed the Indian subcontinent for over a decade, and her hard-hitting stories reveal how environmental destruction impacts livelihoods and biodiversity.

Her book, Marginlands: India’s Landscapes on the Brink, encapsulates the experiences of those living in India’s most hostile environments.

At the root of the climate crisis is the lamentable loss of our elemental connection with land, water and air. It is imperative that we reclaim this connection.

Arati Kumar-Rao

Jennifer Uchendu, Nigeria

Mental health advocate

The ambition of youth-led organisation SustyVibes, founded by Jennifer Uchendu, is to make sustainability actionable, relatable and cool.

Uchendu’s recent work has focused on exploring the impacts of the climate crisis on the mental health of Africans, especially young people.

In 2022, she set up The Eco-Anxiety Africa project (TEAP) to focus on validating and safeguarding climate emotions in Africans through research, advocacy and climate-aware psychotherapy.

Her goal is to work with people and organisations interested in shifting mindsets and doing the hard and often uncomfortable work of learning about climate emotions.

I experience a range of emotions when it comes to the climate crisis. I am slowly making peace with the fact that I will never be able to do enough but that I can, instead, do my best. Showing up in solidarity with others to act, rest and just be, helps me safeguard my climate-induced feelings.

Jennifer Uchendu

Qiyun Woo, Singapore

Storyteller

As an environmentalist and content creator, Qiyun Woo uses social media to share ideas about climate change.

Her online platform, The Weird and the Wild, is dedicated to making climate science more accessible and less scary. It focuses on content to advocate, educate and engage communities on climate change action.

She co-hosts an environmental podcast focused on South East Asia called Climate Cheesecake, which aims to break down complex climate topics into more manageable slices.

She is also a National Geographic Young Explorer.

The climate crisis is complex, overwhelming and scary. We can approach it with fierce but gentle curiosity – instead of fear – so that we can keep our heart soft to care for the world, while sharpening our tools to dismantle what doesn’t work and build what does.

Qiyun Woo

Louise Mabulo, Philippines

Farmer and entrepreneur

In 2016, Typhoon Nock-Ten rampaged through parts of Camarines Sur, Philippines, decimating 80% of agricultural land.

Louise Mabulo defied the devastation by founding The Cacao Project during the aftermath. The organisation aims to revolutionise local food systems through sustainable agroforestry.

Mabulo empowers farmers, dismantles destructive food systems, and champions a rural-led green economy, putting control back in the hands of those who cultivate the land.

She advises international climate policy, where she amplifies rural stories and knowledge. She was recognised by the United Nations Environment Programme as a Young Champion of the Earth.

I find hope in knowing that movements around the world are being built by people just like me, stewarding a future with green landscapes, that connect communities, where our food is sustainable and accessible, where our economies are circular, and are driven by just, equitable principles.

Louise Mabulo

Sarah Ott, US

School teacher

Coming of age in the US state of Florida in the aftermath of 9/11, middle school teacher Sarah Ott says she was vulnerable to misinformation.

Despite being educated in the sciences, for some time she doubted that climate change was really happening.

Admitting that she was wrong was the first step in her search for the truth. Her journey has led her to become the climate change ambassador with the National Center for Science Education.

Now based in the state of Georgia, she uses climate change to teach physical science concepts to her students and raises awareness of environmental issues in her community.

Even though climate change is an “all hands on deck” situation, we just can’t do it all by ourselves. Activism is like a garden. It is seasonal. It rests. Respect the season you are in.

Sarah Ott

Elham Youssefian, US/Iran

Adviser in climate and disability

A human rights lawyer who is blind, Elham Youssefian is a fervent advocate for the inclusion of people with disabilities when addressing climate change, particularly in relation to emergency response to climate incidents.

Born and raised in Iran, Youssefian emigrated to the US in 2016. Today, she plays an instrumental role in the International Disability Alliance, a global network of more than 1,100 organisations representing people with disabilities.

Her mission is to educate decision-makers on their obligations when it comes to the impact of climate change on people with disabilities. She also champions the immense potential of individuals with disabilities in the fight against the climate crisis.

We, as individuals with disabilities, have proven time and again our ability to surmount intricate challenges and find solutions even when none seem to exist. People with disabilities can and should stand at the forefront of the battle against climate change.

Elham Youssefian

Zandile Ndhlovu, South Africa

Freediving instructor

As South Africa’s first black female freediving instructor, Zandile Ndhlovu wants to make access to the ocean more diverse.

She founded The Black Mermaid Foundation, which exposes young people and local communities to the ocean, in the hope of helping new groups to use these spaces recreationally, professionally and in sport.

Ndhlovu is an ocean explorer, storyteller and film-maker. She uses these skills to help shape a new generation of Ocean Guardians – people who learn about ocean pollution and rising sea levels and become involved in the protection of their environment.

Thinking about the number of young voices, rising up to create change in society gives me hope when considering the climate crisis.

Zandile Ndhlovu

Camila Pirelli, Paraguay

Olympic athlete

Although her speciality is heptathlon, it was competing in the 100m hurdles that got Camila Pirelli into the Tokyo Olympics.

Known by her nickname the Guarani Panther, the track and field athlete holds a number of national athletics records, and is a sports coach and English teacher.

Pirelli grew up in an environmentally conscious family in a small town in Paraguay, where she has seen the impacts of climate change up close.

She’s now an EcoAthlete Champion, which means she is committed to using her sports platform to encourage people to talk about climate change and take action to reduce carbon emissions.

I grew up in a town where seeing wild animals was a daily occurrence. Knowing those animals are suffering now due to climate change worries me and makes me want to help.

Camila Pirelli

What is 100 Women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspiring women around the world every year. We create documentaries, features and interviews about their lives – stories that put women at the centre and are published and broadcast on all BBC platforms.

Follow BBC 100 Women on Instagram and Facebook. Join the conversation using #BBC100Women.

How were the 100 Women chosen?

The BBC 100 Women team drew up a shortlist based on names they gathered through research and those suggested by the BBC’s network of World Service Languages teams, as well as BBC Media Action.

We were looking for candidates who had made headlines or influenced important stories over the past 12 months, as well as those who have inspiring stories to tell, or have achieved something significant or influenced their societies in ways that wouldn’t necessarily make the news.

A pool of names was also assessed against this year’s theme – climate change and its disproportionate impact on women and girls around the world, from which a group of 28 Climate Pioneers and other environmental leaders were selected.

We represented voices from across the political spectrum and from all areas of society, explored names around topics that split opinion, and nominated women who have created their own change.

The list was also measured for regional representation and due impartiality before the final names were chosen. All women have given their consent to be on the list.

Back to top

Back to top