Published: Saturday, October 14, 2023, MONITOR

Like most things in life, there is a risk-reward dynamic when wild gorillas are habituated. Back in the early 1990s, Uganda had its first foray at habituation with the Katendegyere and Mubare groups. This was at Buhoma in the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest.

While the economic benefits and ability to put a proverbial finger on the pulse of gorillas are all plain to see, risks—including diseases that can be passed from humans to animals—abound. This, compounded with other risk factors such as poaching, means the Katendegyere group, which was opened for tourism in 1993 with 11 gorillas, had by 1998 decreased to just three gorillas.

In her memoirs, Uganda’s first wildlife veterinarian recounts treating the Katendegyere gorillas that had been afflicted with scabies. Using a dart pistol and blowpipe, Dr Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka meticulously administered doses of ivermectin to the gorillas that were losing hair and developing white scaly skin.

“…We concluded that they (gorillas) must have been exposed when they left the forest to forage for banana plants and the bark of eucalyptus trees on community land, where people put out dirty clothing on scarecrows to scare away wild animals, including gorillas, baboons, and birds,” she writes in her memoirs titled Walking With Gorillas, adding, “Naturally curious, the gorillas may have touched clothing from severely infected humans and the mites burrowed under their skin, and when they groomed each other, the mites quickly spread through the group.”

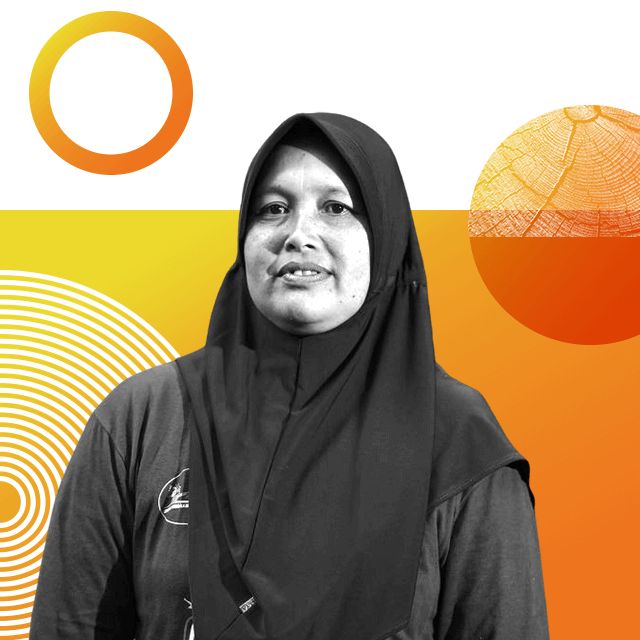

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka, who was born on January 8, 1970 at Mulago hospital in Kampala to Rhoda and William Wilberforce Kalema, grew up surrounded by pets. After attending Kabale Preparatory School in Kabale District, Dollar Academy in Scotland, King’s College Budo in Kampala for O-Level, and Kibuli Secondary School in Kampala for her A-Level, there was always going to be one destination for her, really—veterinary.

And so it was. After graduating as a veterinarian from the Royal Veterinary College (RVC), University of London, she returned home to become the first wildlife veterinarian for the Uganda National Parks (UNP). With time, UNP would rebrand to Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA). Dr Kalema-Zikusoka also set up the veterinary department at UWA.

27 years and counting

Fresh out of vet school, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka had no idea that she would go on to dedicate 27 years and counting treating sick animals in the wild, relocating wandering elephants, gorillas and giraffes, reintroducing giraffes, rescuing orphaned baby chimpanzees, rescuing animals from snares, and testing Cape buffalo for zoonotic diseases.

Zoonotic diseases are transmitted to humans from animals. The transmission can also be vice versa as the scabies cases in the Katendegyere gorillas showed. Dr Kalema-Zikusoka further revealed that open defecation in gardens put “the gorillas at serious risk from common diseases in the community such as cholera and typhoid.”

Besides being a bastion for men, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka would soon discover that the sphere in which she was planting her feet had conservationists who were against veterinarians treating wild animals. The budget that the vet department at UWA ran off also seemed oblivious to the vulnerability of animals such as gorillas to human diseases.

Little wonder, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka ventured into specialised veterinary medicine at North Carolina Zoological Park and North Carolina State University (USA) when she left UWA to pursue her postgraduate studies. Her research was on disease at the human/wildlife/livestock interface. In fact, the non-profit and non-governmental organisation Conservation Through Public Health (CTPH) was born in 2003, with a mission to promote biodiversity conservation. This is by way of enabling people, gorillas and livestock to coexist through improving their health and livelihoods in and around Africa’s protected areas.

“Very few understood that people and animals can make each other sick and that, in turn, this can have enormous impacts on conservation, public health, and sustainable development,” she told Saturday Monitor, adding, “At CTPH, we developed a multidisciplinary approach to address these issues, but because it didn’t fit into a neat category, it was difficult for donors and policymakers to understand the potential benefits.”

Before Covid…

Together with the “lab-leak” hypothesis, a zoonotic episode is hypothesised as a potential trigger of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Covid-19 brought the CTPH concept to a broader acceptance, but wildlife veterinarians have been grappling with the reality of zoonotic disease outbreaks between people and wildlife for as long as there have been wildlife veterinarians…,” Dr Kalema-Zikusoka revealed.

Adding: “Today, there is a global effort known as One Health that aims to help people better understand and respond to the intricate connections between the health of humans, animals, and the environment. By the time the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established its One Health office, Conservation Through Public Health had been implementing the approach for six years. The One Health approach really came into maturity during the Covid-19 pandemic.”

Per Dr Kalema-Zikusoka, Uganda is in the process of developing a National One Health Platform “to work together to prevent, detect, and respond to existing zoonotic diseases, as well as emerging pandemic threats.” Amid the tedious process of applying for funds to run the day-to-day operations and administrative requirements of CTPH, she, with great pride, talks about building capacity among young Ugandans.

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka’s work has been recognised by some of the greatest conservation organisations. She is also the recipient of the Jane Goodall Institute Award for Conservation, among other awards. She has especially developed a strong bond with gorillas so much so that the loss of one left a deep scar.

“Just as we were about to launch the Gorilla Conservation café in December 2017, I received the shocking news that Kanyonyi, after whom our coffee has been named, had died. He had been one of my favourite gorillas, and I’d known him since he was a baby,” she revealed, adding, “Kanyonyi had taken over the leadership of the Mubare gorilla group from his father Ruhondeza five years earlier. …Kanyonyi had fallen off a tree and developed an infection in his hip. He was treated with antibiotics, but he’d fought with a habituated lone silverback, Maraya, and never fully recovered…”

She further revealed that “Kanyonyi had grown up around tourists.” As a silverback and leader of his gorilla group, she added, “he would deliberately set out to frighten tourists to see their reaction—his idea of humour, which was definitely lost on the unsuspecting tourists.”

Where are the women?

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka expresses disappointment that there are very few women running conversation organisations around the world.

“…as founder and chief executive officer of CTPH, I saw that the field of conservation, in particular, had very few women, not only in UWA, but also in Uganda, and shockingly, few women were heading conversation organisations around the world,” she notes, adding, “This means women’s voices are rarely heard. Thus over the years, I have learned that it is often necessary to raise my voice in a room that mainly has men.”

Citing the example of poaching, one of the biggest threats to wildlife conservation, she notes the telling role played by the wives of reformed poachers. This was after they noticed that these women initially “put their husbands under pressure to go into the gorilla’s forest habitat and collect bushmeat, which is also believed to have medicinal properties.”

Family support

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka met her future husband, Lawrence Zikusoka, in North Carolina while pursuing her postgraduate studies. They were engaged by March 2001, with the marriage coming six months later. During their courtship, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka made sure Mr Zikusoka met the mountain gorillas to understand her work.

“As a wildlife veterinarian, I found it challenging to balance parenting with the call of the wild, and support from my family and colleagues was essential,” Dr Kalema-Zikusoka writes in her memoirs, adding, “We have often left our children with my mother and Lawrence’s grandparents when we travel abroad to raise awareness and funds for CTPH…”

It helps a great deal, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka writes, that “when I met Lawrence, he liked the fact that I was happy to be dirty in the bush. …Setting up an organisation with my husband gave depth to our marriage beyond having children, and has come with its own set of interesting opportunities and challenges.”

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says her husband “understood why I have taken our sons to Bwindi from the tender age of two months where Ndhego recognised his first elephant in the national park, and not in a storybook.” She adds: “It has been a joy teaching my children to appreciate and love animals and nature and to have empathy for poorer people we meet in rural areas like Bwindi. The Batwa traditional hunter-gatherers who lived in Bwindi Impenetrable Forest before it became a national park have become their good friends and have taught them many life skills such as making fire in the traditional way.”

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka lives in Wamala in Wakiso District with her husband and two sons. Walking with Gorillas is available in major bookshops in Kampala at Shs100,000, and on Amazon at $18.79 (Shs70,000).

Lessons from gorillas

An advocate of family planning, Dr Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka, Uganda’s first wildlife veterinarian, has learnt to space her children from gorillas.

“I have applied what I have learned from the gorillas to my family, where we spaced our two boys using the same interbirth interval of gorillas of four and half years. This spacing is perfect because the older child is emotionally independent by the time the next baby is born and can even help to babysit and teach the younger child many important life skills.”

She adds: “Our older son, Ndhego, has taught his brother (Tendo Zikusoka) how to play soccer and how to handle animals, and I have always felt safe leaving Tendo under Ndhego’s watch, just like a four-year-old gorilla, who can build its own nest and will be able to play in a healthy manner with its younger sibling while helping its mother to babysit.”

[email protected]

Back to top

Back to top