Author: admin

The Princess Royal interview: ‘I’m not sure that rewilding at scale is necessarily a good idea’

With conservation close to her heart, HRH explains what’s needed to save animals under threat and how the monarchy plays its part

Inside St James’s Palace there is a bit of a flutter about the weather. Her Royal Highness the Princess Royal has several engagements today, and things are not looking good; due to wind, the helicopter might not be able to land at the designated sites, which will make travelling times to and from events longer.

The staff are waiting to be informed by the police, who are in touch with the helicopter pilot. HRH, as everyone seems to call her, has not yet been told.

She has a lot to fit in: directly after our interview, she is off to a meeting about Gordonstoun school, in London, by car, then by helicopter to give a speech at an English Rural Housing Association conference in Bedfordshire, followed by a visit to the Aircraft Research Association, where she will unveil a plaque, then back to St James’s Palace to change for evensong at The King’s Chapel of the Savoy, where she will be reading the lesson for the Royal Victorian Order.

Her day will finish at about nine, when she will be able to eat. Quite often she has a dinner engagement as well. Next week she is going to Mumbai for four days.

Not for nothing is she known as the hardest-working royal. She is involved with more than 300 charities, organisations and military regiments, and last year carried out 200-plus engagements – more than any other member of the Royal family.

Her first official engagement was at the age of 18; shortly afterwards, in 1970, she became president of Save the Children – a position that led to her being nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize – and her work with that charity continues to this day.

Early on, her father, the Duke of Edinburgh, advised her to pick the charities she was interested in – and her interests have multiplied.

But one charity that is particularly close to her heart is the Whitley Fund for Nature, which is why I’m here. Started by Edward Whitley OBE as the Whitley Awards, WFN is now celebrating its 30th anniversary, and the Princess has been a patron for 24 years.

The annual ceremony takes place at the Royal Geographical Society in London and is colloquially known as the Green Oscars; WFN distributes grants totalling around £500,000 to worthy international winners.

So far, £20 million has been awarded to 200 conservationists across 80 countries. And the Princess has never missed a single ceremony, presenting the awards and delivering heartfelt speeches.

HRH is quite probably the most respected member of the Royal family. Her lack of pomp and ceremony and the low-key dedication with which she carries out her duties is much admired. There is no whingeing. She refused titles for her children, Peter and Zara.

She is well known for her dry sense of humour. She is an exceptionally accomplished horsewoman and in 1976 became the first member of the Royal family to compete in the Olympics; she had won Sports Personality of the Year five years earlier. She famously resisted an attempted kidnap in 1974.

She has also become an inadvertent style icon, often rewearing outfits she first wore decades ago, which is both charmingly thrifty and impressive in that she can still fit into them, and she seldom buys anything that is not made in the UK.

She recently made a good-natured appearance on her son-in-law Mike Tindall’s podcast The Good, the Bad & the Rugby and she seems like an all-round good egg.

She has both gravitas and spirit – there was some very moving footage of her accompanying her mother’s coffin on the long journey from Balmoral to Westminster Abbey.

Back in St James’s Palace, Charles, her private secretary, is arranging the chairs, anticipating where she might like to sit. HRH arrives in a striking bright-green suit over a striped silky shirt and heads smartly for a different chair than the one offered.

How did she first get involved with Whitley? ‘That’s entirely Edward’s fault,’ she says in her crisp voice. ‘But the common denominator is Gerald Durrell.’

The Princess grew up reading Durrell’s books and became patron of his zoo in Jersey, part of what is now the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, in 1972. ‘He very kindly asked me to become involved in the zoo – as it was then – in Jersey, and Edward [later became] one of Durrell’s trustees.

‘He and I had similar beliefs in what Gerald was doing. Apart from the fact that Gerald wrote very good books, during his travels he seemed to understand better than most the impact on the populations in which animals lived and the relationship between them and their animals.

‘Being told you have to save this, that and the other is all very well but have you been there? Have you ever tried living in that environment to find out what that means to them? Because the fundamental point is that unless the conservation comes from the local area, it won’t be sustained.’

No one is going to save an animal just because they’re told to. ‘You’ve got to work out how the animals are going to survive with the people who live there, who will be the ones who make sure that it works.’

What was Durrell like? ‘Every bit as entertaining as you would think. His humour but also his understanding of the relative importance of things in other people’s lives was absolutely fascinating – and he was spot on.’

Durrell said he felt ‘sympathy for the small and ugly; since I’m big and ugly I try to preserve the little ones’. He was an expert on captive breeding, with a view to releasing into the wild, and he tended to select animals that were close to extinction, or those that could best be helped, or just ones that were not very charismatic.

‘Yes, not the sexy ones,’ says the Princess. ‘Or the obvious ones. His approach was very holistic. He understood the impact of habitat – not just on one species but how all of the things that lived in that habitat related to each other and that you couldn’t replicate that instantly somewhere else – it was very specific to an area.’

Gerald Durrell died in January 1995, of septicaemia. He was an alcoholic and had successfully received a liver transplant but died of complications it gave rise to. ‘He told me that there was no point doing a transplant because his old liver had got used to being fed all the things he’d been given to eat and drink in order to make deals as he went round the world,’ the Princess says, smiling.

Durrell’s legacy is long. One of his innovations was to establish training for conservationists from around the world. The first trainee went on to become the first director of the National Parks and Conservation Service in Mauritius, and thousands of students from 151 countries have since attended the centre, whose graduates became known as Gerald Durrell’s Army.

This became the title of a book by Edward Whitley, who travelled round the world to assess the progress of some of the trainees and the animals they were conserving – such as the largest eagle in the world in the Philippines and Alaotran gentle lemurs in Madagascar.

To launch the book in 1992, Whitley was invited to give a talk at the Royal Geographical Society, and he asked the Princess to come along. It was at the book launch that he decided to set up the charity.

‘I sat down with Nigel Winser, who was the deputy director of the RGS and a long-time friend, and we designed what became the Whitley Awards on the back of a napkin,’ he tells me. In 1999, Whitley asked the Princess to become a patron. By then, ‘Attenborough was already on board, which encouraged her to think it wasn’t a fly-by-night organisation which would crash and burn’.

The awards focus on community-based conservation projects around the world. In order to qualify, each project has to be up and running – it cannot be a pipe dream. Initially there was only one award; this year there were six – of £40,000 each in project funding – plus a Gold Award of £100,000, given each year to a past winner in recognition of their outstanding contribution to conservation.

‘The reason WFN is so effective,’ says Alastair Fothergill, whose company Silverback made the acclaimed TV nature series Wild Isles, and who like Attenborough is a WFN ambassador, ‘is because its grants are awarded at the very cutting edge of conservation, where relatively modest funds can go a long way. Over the years, the fund has kickstarted the careers of many pioneers who have become leading lights in conservation.’

This year’s projects included safeguarding seabird nesting sites in Mexico; establishing ‘lion guards’ promoting coexistence in Cameroon; and protecting pangolins in Nepal, lemurs in Madagascar, freshwater fish in Lake Victoria and saiga antelope in west Kazakhstan. Each one heavily involves local communities.

In addition, WFN provides continuation funding for award-winners. To mark the 25th anniversary of Whitley, Kate Humble, also an ambassador, and Attenborough hosted an event at the Natural History Museum to help raise £1 million for continuation funding.

‘It was the first really big fundraiser we had,’ says Humble. ‘And one of the donors underwrote the entire cost of the event – so everything raised went into the continuation fund.’

The RGS ceremonies are joyous events. In addition to being presented with their award by the Princess Royal, each winner has a short film made of their work, narrated by Attenborough, screened at the event. ‘I’ve been going for 20 years,’ says Humble, ‘and every year I’m blown away by the winners – what they’ve overcome, what they’ve achieved.

‘You hear so much bad news, and you think, you know what? The world can be OK because people out there are doing this stuff – it’s demonstrable, it’s scientifically rigorous and it’s working. [It’s] an incredibly uplifting and inspiring evening.

‘And every year I watch Princess Anne speak and she never sounds like she’s reading someone else’s words. She cares deeply about what this charity does and what these people who win the awards have achieved – she is not a figurehead just trotting out nice words and providing a photo op. She could run the charity, she knows it so well and cares about it so deeply.

‘I’m not anti-royal,’ says Humble, ‘but neither am I someone who would go and wave a Union Jack. But when I see her I think, frankly you’re worth whatever it is we pay.’

HRH talks with fluency and knowledge on every subject. ‘She’s like a sponge – it’s unbelievable the information that’s stored in her brain,’ said her daughter Zara in an interview for ITV’s Anne: The Princess Royal at 70. ‘It’s quite annoying as well.’

She needs to know a lot because she works with a diverse range of charities, taking in early years, healthcare, microfinance and animal welfare. Promoting collaboration between charities is key. ‘I do a lot of that,’ she says now. ‘I have meetings bringing them together which they all seem to enjoy, though sometimes it’s a bit illogical.

‘Knitting together all the international NGOs is important, but we need to look slightly outside the box – can we do this better, are there ways of helping people to be more sustainable?’

The Princess does occasionally discuss conservation with the King, she says, but she won’t say if they always agree. And her grandchildren? How does she teach them about conservation? (She has five, four girls and a boy.)

‘I don’t see so much of them but making the point that they live in an area which they shouldn’t take for granted is important I think; both my children are aware of that.’

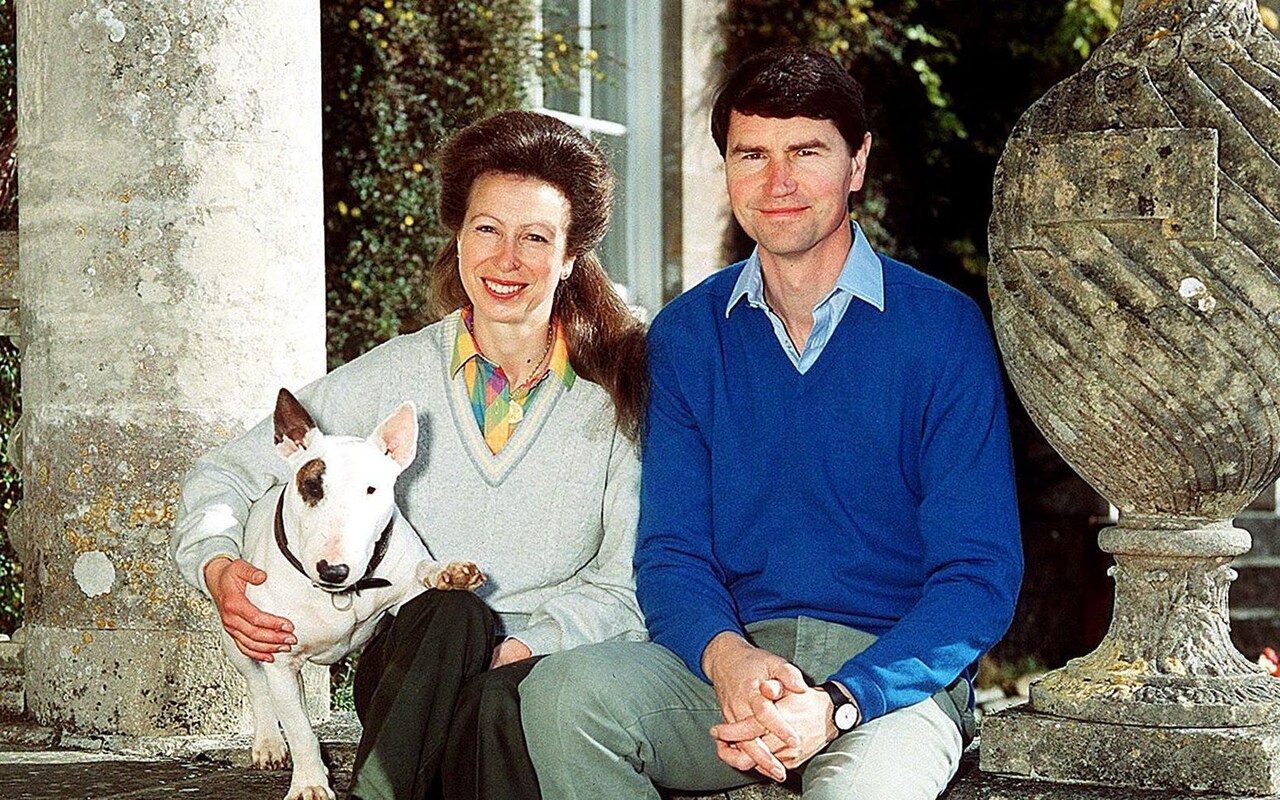

Gatcombe Park in Gloucestershire, where the Princess and her husband, Vice Admiral Sir Timothy Laurence, live in an 18th-century manor with 730 acres of parkland, has some beautiful trees – ‘the ones that survive – quite a lot don’t, we live on Cotswold brash which is not popular with plants; but having said that we have beeches.

‘You’ve just got to live with what’s there and make sure it doesn’t get overwhelmed. I’m not sure that rewilding at scale is necessarily a good idea – it probably is in corners, but if you’re not careful you rewild all the wrong things because they are just the things that are more successful at growing.

‘My biggest row at home is ragwort. Lots of people think that ragwort is absolutely brilliant because butterflies love it, but it’s not good for the horses [it is toxic]. I would say don’t take all the ragwort out, just where the horses are – but it’s quite a delicate balance.’

There are, she says, ‘quite a lot of horses at home, but they’re other people’s as well’. She rides whenever she can. ‘It’s a very good place to observe nature from.’

The Princess supports several horse-related charities, and became patron of Riding for the Disabled in 1971, and president in 1985. ‘It was just becoming a national body when I was invited to become a patron – at that stage I knew nothing about disability but the concept that ponies or horses could make a difference was obviously interesting and I knew about them. No matter what the disability was, the answer was, if they’d like to ride, we’ll give it a go. The commonality of the experience was important.’

Essential things for running a charity, she says, are evaluation and thinking of the long term. She cites the influence of Eglantyne Jebb, founder of Save the Children, ‘who constantly evaluated programmes to see if they were making a difference, whether they were doing the right things and whether people were invested’.

And it’s important to keep projects focused and manageable. ‘I’ve come to the conclusion that scale is the thing that defeats any good idea, because it can get to a size where people can’t cope.’

She has spoken in the past about the huge value of long-term commitment, in terms of the constitutional monarchy as well as in charity work. ‘Seeing things in the long term is a challenge,’ she says now, ‘but maybe part of our [value] – as a family – is long-term continuity, because the long-term view is quite hard to come by. And I think we can do that.’

May I ask what she might have done as a profession in another life? HRH laughs and looks vaguely impatient. ‘You can ask but I’ve no idea.’ Does she ever think about that?

‘Not really, and it’s way too late to have those concerns – in a way the fortunate part of my life has been the broad spectrum, to see so much. Not having a very specific interest has been a bonus, I suppose. We all have ways of doing things and with Whitley it is the practical aspects of what they do, and how to support them [that has been my focus].’

Edward Whitley, a member of the wealthy Greenall Whitley brewing family, set up Whitley Asset Management in 2002, alongside its finance director Louise Rettie, to serve a small number of clients. But there had always been animals in his life – his great-grandfather founded a small charity called the Whitley Animal Protection Trust; his great-great-uncle Herbert was an eccentric animal breeder who started Paignton Zoo.

In Edward’s office is a stuffed cockatoo that belonged to Herbert and a photograph of Mary, his favourite chimpanzee. Mary was famous for riding around on her tricycle and walking the dogs, or taking visitors by the hand and leading them round the zoo.

Edward studied English at Oxford then went into banking, joining NM Rothschild & Sons in 1983. He left in 1990 to write: Gerald Durrell’s Army came out in 1992 and he also co-wrote Rogue Trader, the autobiography of disgraced banker Nick Leeson, and worked with Richard Branson on his memoir.

Whitley is a tall, gentle man who doesn’t like talking about himself but is full of unbridled enthusiasm for WFN, and in particular its royal patron. ‘She transformed the charity – we never would have had the success we’ve had without her involvement. She saw what was possible and really helped us to achieve it, and she inspires the winners to do more. The winners are always pretty amazed at how she cross-examines them and cuts to the chase so quickly when she meets them.

‘She has an encyclopaedic knowledge of the world, and a phenomenal memory, and she is also very funny… And think of her father and the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award – she’s seen what a lifetime of work can achieve.’

In her speech at the Whitley Awards earlier this year, the Princess Royal cited her father, Gerald Durrell and Edward Whitley as the inspirations for her work with WFN. Among winners and their communities, she said, ‘it’s the global ambition to truly make a difference that has been astonishing’.

The awards, she continued, are for ‘the people on the ground, they’re the sharp end… It’s all very well to be here and understand what we think are the challenges, and want to make a difference, but when you meet the people who are actually out front and can turn that into a reality, it’s a real inspiration.’

Over the years, she has visited some of the winners’ projects, when her charity work takes her to those countries, ‘but not as many as I would like’, she says. In Uganda, for example, she met Dr Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka, who was working on improving hygiene in local communities after viruses had spread to gorillas she was managing in Bwindi national park. And in 1997, before she became a WFN patron, she travelled in a boat up the Amazon to see pink dolphins.

‘She was in Colombia for Save the Children and she asked the British embassy to include a visit to the Amazon in her trip – she was very interested in the dolphins,’ says Dr Fernando Trujillo, who went on to win an award in 2007.

‘The British embassy contacted me as an expert on rivers and dolphins. I was a little bit intimidated, and it was raining and I was worried we wouldn’t see any dolphins, but in the end we counted 32 – and she was so excited, every time she saw one she would jump up and down with excitement, and then rein herself in as if she suddenly remembered she was a princess. I could see her love for the environment was very genuine. From that day she was my favourite royal person.’

Another winner, Pablo Bordino, whose picture with HRH had been in the paper in Buenos Aires was flying back to Argentina. One of the flight attendants recognised him and when he arrived at the airport there was a television crew waiting to meet him. It raised the profile of his NGO – which protected marine life and habitats in Argentina – enormously and enabled him to generate further funding. ‘That’s the effect HRH has,’ says Whitley. ‘You can’t quantify it.’

Several award-winners went to the Princess’s 60th-birthday celebrations, including Claudio Padua, a successful businessman from Rio who gave it all up to pursue conservation, training at Durrell in Jersey and moving to a forest in Brazil with his wife, Suzana, and three children.

HRH had been to see them at their headquarters outside São Paulo and had taken an interest in their efforts to conserve the black lion tamarin, a monkey. They had no idea her visit would be such an ordeal, with all the security arrangements. ‘We had a call to ask what kind of security we had,’ says Claudio. ‘I said, “I have an old dog, that’s all.”’

‘She turned up with a security detail and entourage,’ Suzana adds. ‘They wanted to go into the forest to see the monkeys in our Land Rover and her security team asked, “Has this car been checked?” I said it hadn’t and they became very nervous but she ignored them and just got in anyway.’

Years later, the Paduas were invited to Buckingham Palace for her 60th. ‘It was a beautiful opportunity for us,’ says Suzana, ‘and as she came down the stairs she spotted us and said, “Oh how nice to see you. How are the monkeys?”’

The Whitley Fund for Nature is hosting a #PeopleforPlanet biodiversity summit on 6 and 7 November at London’s Royal Institution, where members of the public can hear live from Whitley Gold Award-winning conservationists from Africa, Central and South America, and Asia

Walking With Gorillas Book Signing

Join us in promoting Walking With Gorillas book signing event at Barnes & Noble in Colorado, 11:30am Mountain Time

Gorillas in Our Midst

He told her that Ruhondeza, the 48-year old Silverback leader of the first gorilla group to be habituated for tourism, was spotted alone in a community garden outside the forest. Gorillas that stray into villages are susceptible to human diseases and may destroy cultivated crops.

The warden asked if she would oversee the effort to move the older ape back into the park.

Kalema-Zikusoka was more than eager and more than qualified to save the gorilla. She won the 2022 Edinburgh Medal acknowledging her significant contribution to the understanding and well-being of humanity. In 2021, she was selected as a United Nations Champion of the Earth, and since 2017, a National Geographic Explorer.

Veterinarian Superstar

Kalema-Zikusoka and her team rushed to the scene. Carrying darting gear to tranquilize the ape, they hiked across the hilly farmland for 45 minutes until they found him hiding behind a bush, chewing banana leaves.

“He appeared calm, safer in this community of humans than in his forest home.”

“He appeared calm, safer in this community of humans than in his forest home,” Kalema-Zikusoka writes in her memoir, “Walking with Gorillas: The Journey of an African Wildlife Vet.” He had only days left to live in his fragile state, but she feared returning him to the forest would make him easy prey to territorial silverbacks.

Uganda’s most famous eco-hero you may have never heard of, Dr. Gladys, as she is known locally, is to Bwindi what Dian Fossey, Jane Goodall and Biruté Galdikas were to primates in Rwanda, Tanzania and Borneo, respectively.

Her story has attracted more attention as we approach September 24, International Gorilla Day.

She has been featured on numerous wildlife documentaries, such as “Gladys, the African Vet.” I read her memoir last May, before leaving on my third trip to Bwindi to trek for gorillas and explore the cultural scene, shop for crafts, take a traditional dance class and go on nature walks to support the local economy.

Inspired by Goodall and Galdikas

While studying at the Royal Veterinary College, University of London, Kalema-Zikusoka attended lectures by Goodall and Galdikas, later writing that the two women “inspired and encouraged me to follow my dreams.” In the foreword to Kalema-Zikusoka’s book, Goodall noted that both had a childhood passion for animals and supportive mothers. Goodall also honors Kalema-Zikusoka for overcoming personal and professional hurdles to protect endangered species.

Born in 1970, the youngest of six children, Kalema-Zikusoka grew up during General Idi Amin’s murderous regime. Her family home was filled with pets to try to assuage the grim times.

In 1972, soldiers abducted and killed her father, William Wilberforce Kalema, who had served as a senior cabinet minister in Uganda’s first parliament after the country achieved independence from the British in 1962. “I have always seen my career as a way to continue his legacy, protecting the precious wealth and heritage of Uganda,” she writes.

At 12, she decided to become a vet. While volunteering at the Wildlife Club of Uganda in 1987, a park warden confirmed that mountain gorillas were found to be living in what was then the Bwindi Forest Reserve, a 128-square-mile rainforest about twice the size of Washington, D.C. One of the most biodiverse forests in East Africa, it contains an estimated 324 species of trees, at least 120 species of mammals and 350 documented species of birds.

“You can’t address animal health and the environment without attending to human health.”

Bwindi’s evidence as the world’s second mountain gorilla habitat hastened its designation as a National Park in 1991 and a UNESCO Natural World Heritage Site in 1994.

In 1996, six months into her job setting up a veterinary unit with the Uganda national parks and becoming the first Ugandan wildlife vet, at age 26, Kalema-Zikusoka experienced a breakthrough moment.

While treating a gorilla family infested with scabies from exposure to human sewage and dirty clothing outside the park, she realized, “You can’t address animal health and the environment without attending to human health.”

Indeed, poaching, habitat loss, deforestation and disease had threatened to wipe out the Bwindi mountain gorilla population in the late 1990s. Estimates of their population fell to 300, low enough that the International Union for Conservation of Nature classified the subspecies “critically endangered.”

Kalema-Zikusoka believed a “One Health” approach was necessary to protect the gorillas by improving the health of the local community and environment. To that end, she founded the nonprofit Conservation Through Public Health in September 2003 and appointed her husband, Lawrence, as treasurer. He was a Ugandan telecoms expert she met in graduate school in North Carolina and donated the first $100 to the organization.

On a Zoom call from her home in Entebbe, Uganda, which she shares with Zikusoka and their two teenaged sons, she used the 20th anniversary of the nonprofit to consider its accomplishments and remaining goals.

20 Years of Progress

“At the beginning, everyone thought it was weird,” she recalled, “One Health was a relatively unknown concept when I started advocating for, and implementing, an integrated approach to conservation and health.” Donors at the time focused on either conservation or health. Not both.

Their skepticism ignited her determination. She allied herself to the residents living alongside the park, introducing Village Health and Conservation Teams to administer public health and counsel households on sanitation and hygiene.

She formed the group, Human and Gorilla Conflict Volunteers, affectionately referred to as HUGOs, to herd stray gorilla groups back into the parks. She initiated a treatment program against tuberculosis and established a community based-family planning program that encourages population management.

When Kalema-Zikusoka and her team tracked down Ruhondeza, the mischievous gorilla, and concluded he was too frail to return to the forest, she took her concerns to the Village Health and Conservation Team. She reminded the team that the silverback’s gentle nature helped his gorilla group, the Mubare, to be the first to habituate to the presence of humans in Bwindi, launching gorilla tourism there in 1993.

A Hero’s Funeral

Thanks to him, their lives and futures had improved. When their own elders grew old, didn’t they take care of them? They agreed to allow the declining ape live out his remaining days in their fields. When he died, more than 100 community members gave him a hero’s funeral.

“The kindness and willingness to tolerate Ruhondeza, signified the extent to which conservation efforts had improved in Bwindi,” Kalema-Zikusoka wrote. “Genuine friendship between people and wild animals was indeed possible.”

I trekked the legendary Mubare group in January 2020. After Ruhondeza’s death, his 17-year-old silverback son, Kanyonyi, who Kalema-Zikusoka had known since he was a baby in her early years as a vet, resumed the leadership of the family. He cut a charismatic figure and was known to “deliberately set out to frighten tourists to see their reaction — his idea of humor,” she said.

A New Leader for the Clan

Just five years into his role, Kanyonyi developed an infection after falling off a tree. While being treated with antibiotics, he got into a fight with a competing silverback and died from his wounds in 2017.

Maraya took control of the group and remains their silverback leader today. The stories behind these gorilla groups become narratives, as compelling as human family histories.

COVID-19 closed the park closed for six months in 2020 — a serious blow to Uganda. Tourism and travel account for 7.7% of the country’s economy and more than 60% of the budget of the Ugandan Wildlife Authority, which helps conserve other, less-visited parks, Kalema-Zikusoka said. Travel and tourism employ about 700,000 jobs in Uganda, which has a work force of 18 million.

Poaching Rose as Tourism Fell

“Poaching bush pigs and duikers, a small antelope, for subsistence increased drastically when tourism disappeared,” Kalema-Zikusoka said. Without the daily activities of tourism, hunters felt comfortable entering the park and setting traps, which can maim and kill gorillas. In June, a poacher startled the leader of a gorilla group, causing it to roar in his family’s defense. The illegal hunter lunged at the silverback with a spear, killing it.

Greater security and protective safeguards were implemented for the gorillas. “My team never rested,” recalled the vet. Considered essential workers, they trained rangers, gorilla guardians and village health and conservation teams on mask wearing, social distancing and detecting COVID in gorillas.

They tested the park’s staff and analyzed gorillas’ feces. “I told my team when the pandemic ends, we’re all going to take a month off,” Kalema-Zikusoka said. “It’s never really ended.”

Sgt. Head Guide Augustine Muhangi led my “habituation experience,” where guests spend four hours observing a gorilla group that is undergoing the two-year process of adjusting to the presence of humans. He is 45 years old, grew up in Higabiro Village next to the park and has worked for the Uganda Wildlife Authority for 20 years.

Benefits of Tourism

He still lives in Higabiro Village with his wife, a schoolteacher, and their three children. “Gorilla tourism has improved my village,” he said by email, listing improvements in education, infrastructure and health care. During COVID, he wrote, “gorilla monitoring and protection intensified, and we worked day and night to ensure 100% protection of the mountain gorillas from poachers and COVID-19.” There is no evidence that any of Bwindi’s mountain gorillas caught the virus.

“Gorilla tourism has improved my village.”

COVID-19 revealed the Bwindi community’s dependency on tourism. “We discovered we needed other ways to support the people living next to the park,” Kalema-Zikusoka explained. She wasted no time. Conservation Through Public Health ‘s Ready to Grow Gardens program supplied low-maintenance seedlings, harvestable within one to four months, to over 1,500 food-insecure households, prioritizing residents most likely to turn to poaching out of desperation.

In 2015, Kalema-Zikusoka had created a global, for-profit company, called “Gorilla Conservation Coffee” in response to the low prices farmers received for their beans. The award-winning enterprise pays a premium price to over 500 coffee growers, 120 of whom are women who live next to the national park. Enterprises such as this can help sustain the Bwindi community during low tourist turnouts, she believes.

The Face of Conservation Coffee

A portion of coffee sales go toward saving mountain gorillas. The image of Kanyonyi, the Mubare gorilla family’s lead silverback , remains on the brand, though he died in 2017. Kalema-Zikusoka explains: “His individual story helps tell the larger story about how helping communities that share a habitat with critically endangered gorillas can prevent them from becoming extinct.”

The last census, in 2018, revealed a rise to about 459 mountain gorillas in Bwindi; adding 604 in the Virunga National Park brings the total to 1,063. That year, the IUCN reclassified the mountain gorilla to “endangered,” making it the only gorilla sub-species whose population is growing. Kalema-Zikusoka estimates today’s Bwindi count at about 500, with 24 habituated groups.

“I’m very excited that since I first started working, the numbers have almost doubled,” she said.

And so it seems certain, that walking with gorillas and caring for them is key to helping the people who live alongside them.

Giannella M. Garrett is a writer/photographer who lives in New York City and writes about travel, dance and culture. Her stories have been published in National Geographic, the Washington Post and Conde Nast Traveler.

How Uganda’s First Wildlife vet Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka is Saving Endangered Gorillas

Source: ABC RN / By Nick Baker and Jessie Kay for Saturday Extra | August 8th, 2023

When Idi Amin launched a coup and took power of Uganda in 1971, Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka’s father was among the first victims of the brutal dictatorship that followed.

“[My father] was a senior cabinet minister in the previous government … [so] he was abducted and killed,” she tells ABC RN’s Saturday Extra.

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka was two years old at the time, and she grew up wanting to follow in her father’s footsteps — by devoting her life to helping the country develop and thrive.

On a high school visit to Uganda’s Queen Elizabeth National Park, it became clear how she could do it.

The park had very little wildlife, as much of it had disappeared over Idi Amin’s eight years in power.

During that time, both poaching and the ivory trade were encouraged, with the dictator himself hunting animals in the country’s national parks.

“I thought, ‘Why don’t I become a vet who can bring Uganda’s wildlife back to its former glory’,” Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says.

Changing the attitude to conservation

After high school, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka won a scholarship to study at the University of London Royal Veterinary College.

When she returned to Uganda, she convinced the government to appoint her as the country’s first wildlife veterinarian.

“[But] the attitude towards conservation back then was that animals shouldn’t be touched. They should just be left to natural selection,” she says.

“People looked at me rather strangely when I said we have to treat [injured or sick] animals.”

A key focus for Dr Kalema-Zikusoka was the mountain gorillas of Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, which represent around half of the world’s population of these great apes.

At the time, they numbered just 300 in the park.

And their biggest problem — by far — was humans.

When humans and animals interact

For the Bwindi gorillas, there is a litany of threats from humans.

Habitat destruction and poachers are among these, but what’s less recognised is the health impact of having humans living in very close proximity.

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says humans and gorillas are “always mixing” as there are communities located right on the edge of the park.

And just as humans can pass on illness to other humans, they can also pass on illness to gorillas.

“We share over 98 per cent of our genetic material [with the gorillas] … We’re closely related and we can easily make each other sick,” she says.

An unusual case of scabies

One of the first jobs that Dr Kalema-Zikusoka undertook as government vet was looking into a skin condition affecting the Bwindi gorillas.

The gorillas had rashes and were insatiably itchy — symptoms similar to scabies.

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says there are occasional scabies outbreaks in some less-developed communities in Uganda.

“This gorilla group was spending a lot of time outside the park. So they probably came across dirty clothing … and that’s how they got it.”

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka was able to treat the gorillas with medicine, but one baby gorilla died from the skin condition.

Living side by side

The scabies case, particularly the baby gorilla’s death, was “a big eye-opener” for Dr Kalema-Zikusoka.

“I realised you couldn’t really keep the gorillas healthy without improving the health of their human neighbours.”

But at the time, healthcare options in the communities around the park were dismal.

“[People near the park] had very limited access to good healthcare … the nearest health centre was around 20 miles [32km] away,” she says.

“If someone fell sick, they had to carry them on a stretcher to the health centre.”

So in 2003, she co-founded a non-profit organisation called Conservation Through Public Health, which focuses on the interdependence of human health and that of wildlife, specifically gorillas.

Her approach to conservation is known as “One Health”, which is about “addressing things holistically”.

As part of the work, “teams spread good health and hygiene [messages] and good conservation attitudes and practices”, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says.

She says the approach is working.

After a few years of the holistic conservation practice, human and animal health outcomes changed.

“We found that as people were falling sick less often, gorillas were falling sick less often,” she says.

A 2018 count found that the Bwindi gorilla population had increased by more than 150 — to 459 in total — which moved them from “critically endangered” to “endangered”.

For her work, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka has received praise from the likes of conservation royalty Jane Goodall, who she first crossed paths with in 1993.

Dr Goodall supplied the foreword to Dr Kalema-Zikusoka’s new memoir, Walking with Gorillas: The Journey of an African Wildlife Vet.

“She has made a huge difference to conservation in Uganda, and she is an inspiring example,” Dr Goodall writes.

COVID-19 and gorillas

Gorilla tourism has been part of Uganda for three decades — and it’s brought dollars and development to communities near the park.

Dr Kalema-Zikusoka wants outsiders to come and safely meet the great apes, but it’s not without risk.

“Tourists can bring a fatal flu,” Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says.

Researchers have documented cases where humans have passed on respiratory viruses to gorillas, and while these are often mild, they are sometimes deadly.

So when COVID-19 hit, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka and her team swung into action to further protect the gorillas.

Elsewhere in the world, at San Diego Zoo Safari Park and Prague Zoo a number of gorillas tested positive for COVID-19 after catching the virus from humans.

“During the pandemic, we advocated to the government that everybody should wear masks when they come close to the gorillas, whether it’s the park staff or the tourists or the local community members,” Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says.

“And that really worked. The gorillas did not pick up COVID from people.”

She says the pandemic has made even more people understand the connection between animal and human health, and that “diseases can jump back and forth” between the two.

And while there is still work to be done to improve human and animal health in Uganda, Dr Kalema-Zikusoka says the attitude towards the country’s wildlife — especially the gorillas — has changed.

“The communities really see gorillas as their future,” she says.